If you ask most people in Bed-Stuy’s District 16 why they think enrollment is falling, chances are they’ll point to charter schools: privately managed public schools, which have been on the rise in New York City for more than a decade.

Charter schools were originally dreamed up to be laboratories for innovation in public education. Instead, many see them as a threat — competing with neighborhood schools for space, resources, and kids. Is this really a zero-sum game?

In this episode, we talk to parents and educators on both sides of the district-charter divide to explore why charter schools seem especially polarizing in a Black neighborhood like Bed-Stuy, and what the growth of charter schools means for the future of this community.

CREDITS

Producers / Hosts: Mark Winston Griffith and Max Freedman

Editing & Sound Design: Elyse Blennerhassett

Production Support: Jaya Sundaresh, Ilana Levinson

Music: avery r. young and de deacon board, Chris Zabriskie, Blue Dot Sessions, Ricardo Lemvo

Featured in this episode: Rafiq Kalam Id-Din, Steve Brier, Anika Greenidge, NeQuan McLean, Nikki Bowen, Oma Holloway, Rahesha Amon, Odolph Wright

School Colors is a production of Brooklyn Deep, the citizen journalism project of the Brooklyn Movement Center. Made possible by support from the NYU Metropolitan Center for Research on Equity and the Transformation of Schools and the Carnegie Corporation of New York.

EPISODE NOTES

Subscribe to Brooklyn Deep’s Third Rail podcast

RSVP here for the November 21 meeting of nycASID featuring a discussion with Mark and Max, moderated by Natasha Capers

Ember Charter School for Mindful Education, Innovation, and Transformation

We received the following note from James Merriman, CEO of the New York City Charter School Center, in regards to the testimony of Odolph Wright, Parent Coordinator at P.S. 5: “[Charter school students] come back and they come back after… October 31st. That [charter] school got the money. [The students] come back. We don't get the money.”

Charter schools get their per pupil allotment in six bi-monthly payments from NYCDOE and it is measured in # of weeks actually enrolled in the charter school (which in turn is measured by attendance). In other words, for a particular student the formula is effectively # of weeks enrolled divided by total number of weeks in the school year multiplied by the total per pupil amount for that year. It’s all laid out in the statute, the Charter Schools Act, and with much greater specificity in regulations promulgated by NYSED (8 NYCRR 119.1.) As such, if a student returns to a district at any time, they stop receiving money for that student as soon as that student re-enrolls in the district. In turn, this means that there is no incentive to return kids to the district on November 1 for monetary purposes and, not surprisingly because there is no incentive, no one has ever documented this happening (which is not to say that there isn’t a larger issue of more difficult students returning to the district from some charter schools though this too is complicated). It is though probably the most enduring myth out there despite being completely falsifiable.

However, the administrator at PS 5 is not wrong in one aspect (and frankly the only one that matters to the schools themselves generally and to him specifically). While I’m pretty sure that NYCDOE does true up funding to actual enrollment in its own schools one more time (I believe 12/31), after that it does not. If a traditional district schoolhas new students, returning students or fewer students, its school based funding remains the same. In other words, the charter schools don’t keep the money when a student leaves but if that student goes to a district school after 12/31, NYC does not distribute that money to the school! Why? Who knows.

images

TRANSCRIPT

MAX FREEDMAN: The first time I ever visited Ember Elementary School in Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn, I walked into a classroom set up as a living statue gallery. All around the room, there were children in costume, frozen in place, trying not to fidget as they waited for me to approach. So I walked up to the first statue and tapped him on the shoulder.

GEORGE JUNIUS STINNEY JR: (clears throat) If the white mans didn't call me a negro would I be here right now? If the white people didn't judge me by the color or the texture of my skin would I be here right now? If the Whites didn't hate me would I be here right now? No. The answer is truly no. Hi my name is George Junius Stinney Jr. I was born October 21st 1929 in South Columbia, Carolina. I died June June 16th 1944 when I was 14 in my hometown of South Columbia, Carolina because I was executed that day by an electric chair. Here is the story of how it happened. One day…

MAX: When he was finished with his story, I went on to the next statue.

SOJOURNER TRUTH: Hello everyone. My name is Sojourner Truth and when I was nine I was a slave working for people that I did not know.

MAX: And the next.

MICHELLE OBAMA: Good evening ladies and gentlemen. My name is Michelle Obama.

JULIUS ERVING: Hello everybody. My name is the doctor. Julius Erving a.k.a. Dr J.

URSULA BRANDS: Hi my name is Ursula Brands. I'm one of the most powerful businesswoman in the world.

NAT TURNER: Hi I am Nat Turner.

SHIRLEY CHISHOLM: My name is Shirley Chisholm.

MALCOLM X: Hello my name is Malcolm Little. But many of you guys know me to be Malcolm X.

MAX: In the back of the classroom, there was one student lying face down on the floor. I had to lean all the way down to tap him on the shoulder and he stood up.

ERIC GARNER: My name is Eric Garner. I have been placed in a chokehold which was banned from the NYPD. My face was flat on the ground and i was saying I can't breathe eleven times. One hour later I had died and I realized that wasn't fair. But now I want to ask you a question. What would you do if you see something like that happening in your community? Would you just stay there, walk away, or do something?

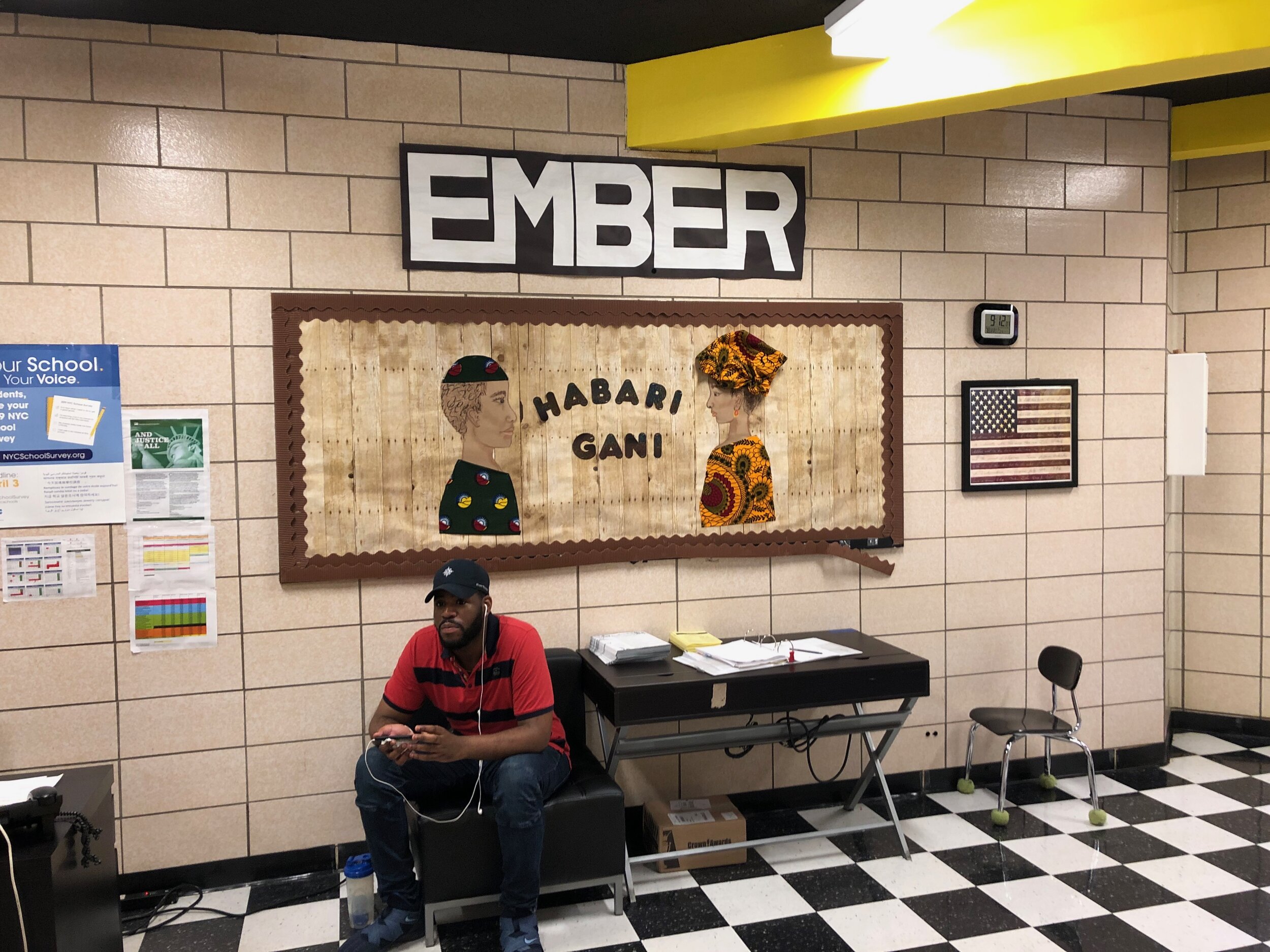

MARK WINSTON GRIFFITH: At Ember, they call their classrooms “schoolhouses,” and each schoolhouse is named after someone like the Black nationalist Marcus Garvey, or Sundiata Keita, 13th century emperor of Mali, or ideas like revolution or venceremos, which means in Spanish, “we will overcome.” Students and teachers greet each other with the words, “Habari gani.”

RAFIQ KALAM ID-DIN: Habari gani literally means what's the good word.

MARK: The founder of Ember is Rafiq Kalam Id-Din.

RAFIQ KALAM ID-DIN: It's a Swahili greeting. And almost all the responses are about community are people are fine our people are great. our nation our neighborhood our city is good. And so even that as the greeting we use Habari gani we use Peace. They're designed to send that same underlying message about well what is a kind of community we want to be in to kind of do this work.

MARK: This Swahili greeting, the talk about Black nation-building, it all draws on the lineage of struggle for self-determination in this neighborhood that we’ve chronicled in this series, from community control in Ocean Hill-Brownsville to The East.

MAX: So you’d think a school like this would be embraced here. And it has been, by some. But others see it as a threat.

MARK: Why? Not Because it’s too Black, too strong; But because it’s a charter school.

MARK: This is “School Colors,” a podcast from Brooklyn Deep about how race, class, and power shape American cities and schools.

MAX: Bed-Stuy’s District 16 is losing students at a rapid clip. And If you ask most people in the district what they think is happening, chances are they’ll point to charter schools.

MARK: Charter schools are privately managed public schools. They were originally dreamed up to be laboratories for innovation in public education. But in an ecosystem where resources are scarce and traditional public schools are an endangered species, for many, charters look like predators.

MAX: For the last 15 years, as enrollment in District 16 has been going steadily down, the number of students in charter schools has been going steadily up, to the point now where enrollment is almost even.

MARK: And though charter schools can provoke controversy anywhere they show up, they seem especially polarizing in Black neighborhoods like Bed-Stuy. The caricature of charter schools is that they come in from the outside to impose the priorities of white philanthropists and corporate donors;

MAX: That they enforce punitive discipline and obsess over test prep;

MARK: That they undermine a teachers’ union that has provided many Black people with good middle-class jobs;

MAX: That they take resources from public schools and leave the most vulnerable children even more vulnerable;

MARK: And ultimately, that they compromise the public safety net that most Black folks still rely on to educate their children.

MAX: So is all this stuff true? Yes and no.

MARK: But real talk? There are reasons why charter schools can be appealing. Simply blaming charter schools for the decline of traditional public schools ignores the deep dissatisfaction that many Black parents have with their public schools, and the profound yearning for alternatives of ANY kind.

MAX: In other words, if there wasn’t a powerful desire for change, the charters wouldn’t be here.

MARK: Ironically enough, both sides -- charter and traditional public school advocates -- have claimed the mantle of civil rights, racial justice, and self-determination. Both sides say they’re the underdog, they’re the ones under attack.

MAX: Can they both be right?

MARK: If you want the kind of self-determined education in Black neighborhoods like we saw in Ocean Hill-Brownsville, is a charter school like Ember the only way to get it?

MAX: Or are charter schools writ large destroying whatever’s left of community control?

RAHESHA AMON: It was not a fair game.

NEQUAN MCLEAN: Some parents like shiny things. And if you can show them something shiny that’s the way they’re going to go.

ANIKA GREENIDGE: They don’t want to deal with badass kids. They don’t want to deal with that.

RAFIQ KALAM ID-DIN: This is what happens when you don’t have people who you’re trying to serve as a part of the solution.

RAHESHA AMON: When the music changes so has your dance gotta change. The music has changed.

MARK: This is Mark Winston Griffith.

MAX: And Max Freedman.

MARK: Welcome back to “School Colors.”

RAFIQ’S STORY

RAFIQ KALAM ID-DIN: I came from generations and generations and generations of poverty no one in my family's history ever was prosperous. I'm the first person in my family's generation me and several of my siblings, we’re the first people to experience any kind of economic success in that way.

MAX: Rafiq Kalam Id-Din grew up in Philadelphia. He’s one of 10. His mother and father were teenage parents.

RAFIQ KALAM ID-DIN: While they never escaped the poverty at least the economic poverty. They certainly escaped the mental and intellectual poverty. That's why I'm here.

MARK: His father had been in and out of jail as a young man, until he joined the Nation of Islam. The Nation pioneered independent Black education going as far back as the 20s. By the 70s, they ran their own schools all over the country -- including the one Rafiq attended, in West Philly. But when he was around 10 or 11, his family started falling apart.

RAFIQ KALAM ID-DIN: My oldest sister committed suicide. Um. My mother had been battling mental illness uh and then her schizophrenia really exploded around this time and my father's uh drug addiction began. As you can imagine in response to losing a child. But it just the floor fell out from from underneath us. Um. And my parents weren't there. They just weren't available. But. The foundation that commitment to education and self discovery and self empowerment. That stayed. That had taken root.

MAX: They left the Nation of Islam and Rafiq had to go to public school. He and his siblings lied about their address so that they could go to schools in an upper-middle class neighborhood. He was in the 8th grade. It was a rude awakening.

RAFIQ KALAM ID-DIN: First of all I'd never gone to school with white people. And. At first I'm thinking wow you know maybe I have a lot to catch up on but. I don't know what passed for education in the public school system. But they were not ready for us. Not at all.

MAX: He says they’d give him a reading test, he’d get a 97, they’d say he cheated. They’d put him in an advanced reading class, he’d tell them he’d already read Macbeth and Cymbeline, they’d say he was lying. He says he had the highest GPA in the school, and they changed the rules so that he couldn’t be the valedictorian.

RAFIQ KALAM ID-DIN: I'm the I’m the poorest kid in this class. It just occurred to me why would you want me to feel the least empowered. Right. And so that then became like I knew this is what public education was about. Public education was about putting up roadblocks denying any kind of value that black kids brought to it.

MARK: He went on to a selective public high school where he and his siblings were no longer the only students of color, but:

RAFIQ KALAM ID-DIN: But what I didn't know was that all the students who started with us weren't going to finish with us. If you couldn't keep up you had to leave. Who was leaving en masse. The black kids. Another lesson in my education.. Who are these institutions for.

MARK: These institutions may not have been meant for Rafiq and kids like him, but he grabbed for every opportunity he could.

MAX: Fast forward a few years: Rafiq became a corporate lawyer specializing in international finance, then he left Big Law to run an educational nonprofit. But he had always wanted to start his own school.

MARK: He started dreaming of a school with an unorthodox leadership structure, inspired by his experience practicing law.

MAX: Most schools are managed by an administration: principal, assistant principal -- in other words, folks who don’t teach (even if at one point they did).

MARK: At a law firm, on the other hand, decisions are made by the partners, who continue to practice law even as they lead the organization. That’s what Rafiq wanted to replicate in a school setting: he calls it a “teaching firm.”

RAFIQ KALAM ID-DIN: And so it was really about designing an organizational structure that would be truly teacher led.

MARK: And he called his school… Teaching Firms of America Professional Charter School. (Ember came later.)

RAFIQ KALAM ID-DIN: I'm just not a creative person so I was like wow our model is called a teaching firm so well let's just go with that.

MARK WINSTON GRIFFITH: I don’t know if anyone who would meet you would say you’re not a creative person but anyway we’ll go with that.

RAFIQ KALAM ID-DIN: I mean the name is proof enough right.

MARK: Ironically, even though this model would put more power in the hands of teachers, he knew the teacher’s union would never let him try it out. Which is why:

RAFIQ KALAM ID-DIN: It had to be a charter school. There was no other way. I couldn't do this in the context of the union contract of a traditional school. It had to be a charter school I needed the freedom to be able to innovate in the way that the charter school framework gives us.

CHARTER HISTORY

MAX: The charter school framework has an unlikely godfather: Albert Shanker.

ALBERT SHANKER: I'm not opposed to community participation or even community control. I am against, what in those days, was called total community control, which means that we can do anything we want and people don't have any civil rights or human rights.

MARK: Remember Al Shanker? He was the president of the New York City teachers’ union during the strikes of 1968. A few years later, he became the president of the national teachers’ union, a position he held until his death.

MAX: In 1988, Shanker recognized that public education was stagnating and endorsed the idea of a new kind of public school. Much like Rafiq Kalam Id-Din, he wanted to empower teachers: free them from the constraints of the central bureaucracy to create laboratories for innovation and experimentation from which other public schools could learn.

MARK: But what Shanker had in mind was very different from what charter schools became.

MAX: The very first charter law, in Minnesota, established a template for schools that would answer to the state instead of local school districts and be encouraged to compete with district schools.

MARK: New York State got its charter law in 1998 and the first charter school opened in New York City in 99.

MAX: Charter schools really exploded under Mayor Michael Bloomberg: part of his overall strategy to encourage competition and school choice. Today, there are 260 charter schools across New York City, educating about 11% of our students.

MARK: The word “charter” basically just refers to the piece of paper that authorizes one of these schools to operate. There’s nothing about charter schools that says they have to be any particular kind of school.

MAX: But as the sector grew, most of these new schools had a couple of things in common: a strong emphasis on discipline and opposition to teacher’s unions.

MARK: (Al Shanker would be rolling in his grave.)

MAX: Let’s take these one at a time.

THE UNION

MARK: It’s impossible to deny that there has been a decades-long assault on organized labor in this country. But teachers’ unions in particular have suffered from the reputation that they protect teachers at the expense of children and stand in the way of innovation. That reputation has fueled the charter school movement. And at least in New York City, that reputation owes a lot to what happened in Ocean Hill-Brownsville.

MAX: If you haven’t heard Episodes 2 and 3 of this podcast, let me briefly recap: Ocean Hill-Brownsville, just southeast of Bed-Stuy, was the site of an experiment in community control of schools. The teachers’ union believed the local school governing board had abused its powers, so they went on strike citywide in the fall of 1968. This was seen by many as a strike not against management, but against students and families of color. When the dust settled, the union mostly came out on top. But as historian Steve Brier says, the union may have won the battle, but in some ways they lost the war.

STEVE BRIER: The failure of community control fractured, the very real connection between teachers and communities, particularly communities of color. That’s a humpty dumpty that’s never been put back together again. The residue of bad feeling about the union and its relationship to the communities is still there. Whether they remember the specifics, it’s a collective consciousness about what happened.

MAX: The question is, have they changed?

MARK: In the immediate aftermath of Ocean Hill-Brownsville, the union worked to build bridges with communities of color

MAX: or to co-opt the movement, depending on who you ask

MARK: by bringing many of the parents who had worked in community controlled schools into the union as school aides, or paraprofessionals. Today, there are many more Black teachers and Black leaders in the union than there were back in the day. And District 16 has a higher percentage of Black teachers than any other district in the city.

MAX: And yet the union has never been able to convince a lot of Black families that they’re willing to fight for them. And that’s partly why they haven’t had the popular strength to successfully fight back against the spread of non-unionized charter schools.

MARK: After repeated attempts, no one from the United Federation of Teachers would agree to talk to us for this podcast. That seems telling. And what we heard in our reporting was that the union is top heavy, and simply not interested in supporting popular organizing at the school level by their teachers.

MAX: If teachers felt empowered to fight for what they and their kids need in the classroom and not just for what leadership says is in the union’s interest, maybe solidarity could start to be rebuilt. That’s what we’ve seen recently in Chicago, where the teachers’ union went on strike not just for their own wages and benefits, but calling for affordable housing for their students. This is extremely relevant in New York City, where 1 out of every 10 students citywide has been homeless in the last year.

NO EXCUSES

MARK: But what unified the charter school movement wasn’t just hating on the teachers union. Many of the schools at the vanguard of the charter movement shared a common culture often referred to as “no excuses.”

MAX: On paper, “No Excuses” sounds alright: no excuses for failure, no excuses for letting kids down. But the flip side of “no excuses” is that there are no excuses for fidgeting, no excuses for not conforming to this one particular way of expressing yourself. No excuses for being late to school. Again, there’s nothing inherent in the mechanism of charter schools that says they have to be this way, but because the first generation of charter schools broke out the gate with high test scores using this model, there were a lot of copycats.

MARK: “No Excuses” clearly does have a strong appeal and long history in this community. If you see the stress and chaos of Black urban life as THE impediment to school learning, “tough love” is a natural response. Take the example of Frank Mickens, the legendary principal of Bed-Stuy’s Boys and Girls High School — which was never more popular than when Mickens used his “no nonsense” approach, along with a hammer and bullhorn1, to enforce strict codes of conduct.

MAX: Anika Greenidge grew up in Bed-Stuy, and attended a public school in District 16, but when she became a parent, she did not want a public school for her son.

ANIKA GREENIDGE: Cause I went to public school and kids used to run amok . I mean you had your teachers who cared. And then you had a lot of teachers who really didn't care.

MARK: So she put her son Jalen in a charter school.

MAX: Most charter schools in New York are nonprofits, but this one happens to be part of a national network run by a for-profit company and tied to a billionaire friend and ally of Trump’s Education Secretary Betsy DeVos.

MARK: But Anika and her husband didn’t know about any of that. They thought:

ANIKA GREENIDGE: Oh maybe there's more structure. It still has the feel of a public school setting but it's a little bit more. I don't want to say strict but. Uh.

MARK WINSTON GRIFFITH: Discipline?

ANIKA GREENIDGE: Yes.

MAX: And they were attracted to some of the qualities that made it feel like a private school, but free.

ANIKA GREENIDGE: All of the extra miles that you had to go to try to get in and oh you're on a waiting list and this and that. I just felt like the exclusivity of charter school and what they had to offer would be better than. I thought it would be better. I thought.

MARK: Jalen struggled with reading, so eventually he was placed in a special early-morning reading program with a new teacher.

ANIKA GREENIDGE: She was Caucasian and she was very mean. I actually liked her in the beginning because I said OK she's not going to play with the kids. They're going to do what she says. But she started to pick on my son.

MARK: Many charter schools are notoriously strict about punctuality, putting high standards on students and their parents alike.

ANIKA GREENIDGE: Sometimes we would be late to school. And he had to be there as you know the charter school. If you're one minute late they're closing the door you have to go around this way and do this and do that. Backflips.

MAX: The backflips didn’t stop at the doors to the building; they continued in the classroom.

ANIKA GREENIDGE: He would come two minutes late one minute late and she would fuck with him she would mess with him. One of the principals assistant principal she noticed my son walking down the hallway with his head down and she said Jalen where are you going. What happened. He said I can't get in the class. And she said Well why not. And he said Well I'm late. So she won't let me in. Ultimately the teacher would let him in. But then he would have to sit in the back. He can't raise his hand because he was late and da da da da da. And it just really pissed me off.

MAX: So she got a meeting with this mean Caucasian reading teacher.

ANIKA GREENIDGE: And she was like “well like I told you before if he can't be in that class on time. This is a special class for children that I've created.” I will never forget she said that. And I was like “Who the fuck do you think you are.” And the principal was looking at me and was like “Calm down calm down.” I said “I'm calm I'm trying to stay as calm as I can be.” I said “but she feels like she runs the school because she created this little program in the morning for the children who are struggling.” I guess she was trying to like push it to me and say well like you as a parent are not doing your job. And I was like I'm doing everything I can. I'm looking for tutoring I'm looking for free tutoring paid tutoring whatever I can do. So my son can go to third grade. But you're not gonna belittle me and you're definitely not going to belittle him. So. At that moment I was done.

MARK: She left that school and went to her neighborhood public school -- what happened there, we’ll find out in the next episode.

MAX: But long story short, she now sends her son to a different charter school, part of a different network.

ANIKA GREENIDGE: It's a nice school. It makes you think that. Oh my God this is so nice and beautiful and.

MARK WINSTON GRIFFITH: Nice facility.

ANIKA GREENIDGE: Yeah. But. He tells me everything is literally on a time schedule mom like if we don't eat our food in time. And he's a slow eater. He looks through the food he sifts through the food. They will dump it in his face like garbage garbage garbage. Come on let's go. We got to go.

MARK: And she has noticed something that almost all the teachers there have in common.

ANIKA GREENIDGE: Everybody's probably younger than me or my age. What's happening. Like everybody literally just graduated from college that that works there.

MAX: She thinks the age and inexperience of the teachers has something to do with the emphasis on strict discipline.

ANIKA GREENIDGE: To me the teachers go in um. Implementing like rules rules rules because. They don't want they don't want to deal with bad ass kids. They don't want to deal with that.

NEQUAN MCLEAN: My son in. Kindergarten or maybe first grade first grade was suspended for tapping on the table.

MAX: This is NeQuan McLean, president of the Community Education Council for District 16. He’s the leader of the official parent body for traditional public schools in this district, and even he tried putting one of his sons in a charter school.

NEQUAN MCLEAN: This is a brilliant young man. Now we see why he was tapping because he plays like every instrument. But because they didn't tap into that and they wanted him to walk on a straight line. This is a student that ever since he took a test has been a level four level three level four. But wasn't given that opportunity because. They claim something was wrong with him because he was tapping on the on the desk.

MARK: Actually, I’ve experienced this kind of thing myself. When we couldn’t get into the public middle schools of our choice, my wife and I, in an act of desperation, enrolled our older son, Manoc, in a brand new independent charter school.

MARK: What we didn’t realize was that the young white staff was experimenting with a kind of zero tolerance approach on a student body that just happened to be 98% Black and brown, including many from public housing. For instance they had an elaborate system of hand signals for “proper” volume in the hallway. He talked too loud once, and boom, he got detention. When someone pulled a prank in the school and no one confessed, Manoc and his entire cohort of boys were all held responsible and punished.

MARK: So barely two months into middle school, my son, who had never been in any trouble before or since, faced detention three times. I swear, it felt as though my 10 year old was getting primed for the carceral system. Needless to say, we left that school.

MARK: I think even folks who want more discipline are still going to be particularly sensitive when it comes from a white-led and sometimes corporate funded enterprise that seems to champion the view that Black bodies need to be controlled, policed and micro-managed. There’s something about it that pushes buttons that are generations and centuries deep. Rafiq cut to the heart of it.

RAFIQ KALAM ID-DIN: You'll get no debate from me that discipline is important but it's really discipline of the mind that's important not of the body. Right. And when discipline is externally imposed we called that slavery indentured servitude. Right. And now we call it incarceration.

RAFIQ KALAM ID-DIN: And I think sometimes my peer charter school institutions I think they don't have the historical narrative right. So When we do that to a group of people who have been enslaved who have been segregated and marginalized. It actually repeats a trauma. And I just think that like on some level is something that they're not aware of but we know right because this is an institution run by black people. And so we know our history.

MAX: But ten years ago, when Rafiq was trying to open a charter school, he found himself swimming against the tide. “No excuses” was all the rage among people putting their money and power behind new charter schools.

RAFIQ KALAM ID-DIN: They thought that they had these schools because they were getting outsized test results. That that had to be the way. And I wasn't convinced. I wasn't convinced that test prep actually gave us a true sense of what student success was. It simply said that they responded to the prep. Not necessarily the underlying thinking. Um. And I was definitely not going to implement the behavior strategies that they would they needed in order to produce those test prep outcomes. They were very draconian lots of control students had to sit a certain way and walk a certain way. And I visited many many charter schools at that time and I knew for a fact that that was not the kind of environment that I was going to create for students.

MAX: In order to open his school, his charter had to be approved by the city’s Department of Education, then the state. Rafiq says that even though the charter boom was at its height, the authorities were always skeptical of what he was trying to do.

MARK: Because of his refusal to focus on test prep, because of his emphasis on black culture, maybe even just because of who he was.

RAFIQ KALAM ID-DIN: What they thought was necessary I think was that the culture that these students came from that they were a part of that that had to be left behind. That was a big part of their narrative. You need to leave your neighborhood. You need to get out from where you were. Really discarding all of the value the history the richness that was really a part of who the lives that children were from and the histories that they were from and that they were continuing to be a part of. And so I think. This is what happens when you don't have people who you're trying to serve as a part of the solution.

RAFIQ KALAM ID-DIN: There is a fundamental disbelief that black and brown people actually have the solutions to these problems in their community. That they believe that only outsiders can solve these particular problems. And so it was very difficult for us. We were turned down the first time we went through the process. We were told that we were too innovative.

MAX: But they he were as not deterred. They revised their charter application, and the second time was the charm. But after their charter had been approved, they had to find a home.

CO-LOCATION

MARK: Across New York City, charter operators have concentrated in poor communities of color. Charter leaders say they’re simply going where there’s demand and space. And of course, there IS demand for change in neighborhoods like Bed-Stuy where, historically, families have been most poorly served by their public schools. But the question of space is more complicated.

MAX: New York state law says that when a new charter is approved, the city is required to either find them space in a DOE building -- or to pay their rent in a privately owned building. When the city looks around for space in buildings they already own, they find it in under-enrolled districts like 16.

MARK: But Rafiq didn’t just “end up” in Bed-Stuy because there was space. This is where he wanted to be. Because he saw himself as upholding the legacy of Ocean Hill-Brownsville.

RAFIQ KALAM ID-DIN: Black people made a decision that they wanted to educate their own kids in their own community with their own people. And the backlash was ferocious. That experience was very similar to the experience that I had in Philadelphia. Just being as a part of the Nation. And so I was looking for those parallels. I was looking for a place that had a similar historic root because I knew that my message would be appealing there. I still had to ask for permission.

MARK: For all his Black nationalist bonafides, Rafiq was still an outsider here in Bed-Stuy. So he worked hard to make sure that the local establishment knew he was one of them and shared their values.

MAX: If you’ve been listening to this podcast, these names might sound familiar.

RAFIQ KALAM ID-DIN: When I got here I met with Al Vann. Dr. Lester Young. I met with Brother Jitu Weusi before he passed away. I talked to all our local electeds Annette Robinson. I spoke to everybody who had been here who had been on the front lines of those fights in those battles. For self-determination. This was ground zero for that.

MAX: When Rafiq’s new school was set to be co-located with a traditional public school in District 16, there was a public hearing. Now this other school had once housed the only gifted and talented program in the district -- a program that was closed by the same Bloomberg administration that had paved the way for all these new charters. So a bunch of teachers and parents and students showed up to protest.

RAFIQ KALAM ID-DIN: And Al Vann came and he spoke and he said I may not support charter schools in general. He said while our critiques of how these schools are coming into our communities he said that's not these brothers. He said they are here with something that we need and we are going to support them. And it silenced everybody.

MARK: It’s no small thing that Rafiq got Al Vann, folk hero of community control, to speak for him at this hearing. Especially because Al Vann, who once fought the teachers union, has been their staunch ally for the last thirty years -- and consequently, an opponent of charter schools. The way Rafiq sees it, the union never really changed its stripes. He says the union’s rules around teacher tenure and work hours continue to set the wrong priorities and values. And he started to see the results as soon as his school moved into the top floor of a District 16 school building.

RAFIQ KALAM ID-DIN: There were fights all the time. At some point we had to send our staff downstairs so that the fights were happening and our kindergarten or first grade students were getting kind of caught up in the middle of that. Like conflict happens amongst students. But when it's widespread and prevalent so many times you would just see adults standing by not doing anything. And that kind of passivity isn't good for any of our kids. And so I would say that there to some degree is a level of apathy that I see in what. Is expected from our kids. There are teachers in each of the buildings where we been co-located where they are doing really amazing work. But they are islands. They are islands in a sea of apathy and disengagement.

MARK: But the alternative to apathy and disengagement was never going to be restrictive discipline.

RAFIQ KALAM ID-DIN: Our students are coming to us with so much trauma. So much trauma. Over half of our student population comes with severe trauma exposure. And so the best place to heal is not in a place of turmoil right. It's gonna be in a place of peace. And so that's what we try to really nurture and cultivate here.

MARK: He didn’t start out thinking much about trauma, but after Rafiq and his partners started to realize how pervasive trauma was among their student body, they decided to pivot their model.

MAX: And as the school evolved, they rebranded: from Teaching Firms of America to Ember Charter School for Mindful Education, Innovation, and Transformation.

RAFIQ KALAM ID-DIN: Everything stops for our mental health. Our quote unquote academic instructional lessons. They don't take precedence over the mental health engagement. That's the priority. And so because of that I think we've been able to actually produce the gains. Now it may take a bit longer but the gains are pretty dramatic. Especially since students who've been with us for more than four years.

MAX: Rafiq always envisioned Ember as a K through 12 school: in other words, a complete educational ecosystem. Every year since opening, they’ve added another grade. They now have an elementary and a middle school, each co-located with a different traditional public school in District 16.

EXCELLENCE GIRLS

MARK: But less than half the charter schools in New York City are independent, like Ember. The rest are run by, or affiliated with, Charter Management Organizations, or networks.

MAX: And these networks are most associated with the image of charter schools that Ember’s trying to subvert: antiseptic, obsessed with test prep, staffed by young white teachers with expensive degrees who yell at Black and brown kids all day.

MARK: Yeah, I know that sounds extreme. But actually, it’s because of this image that the language of “No Excuses” and “Zero Tolerance” has really fallen out of favor in the last couple of years, even within the charter world.

MAX: So when I asked Nikki Bowen, principal of a charter school called Excellence Girls, if she identifies with “No Excuses,” I wasn’t super surprised when she immediately said no.

NIKKI BOWEN: No. We've moved away from that model. Just because like. Every individual child every individual family every different teacher has different needs. And so I think like no excuses has this like negative connotation in that there is no place for differentiation. Right. Or mistakes.

MARK: Excellence Girls is part of the Uncommon Schools network, which operates three schools in District 16. As the principal, Nikki Bowen herself defies some of the stereotypes about charter networks: she’s a Black woman, born and raised in Central Brooklyn.

NIKKI BOWEN: If they make a mistake we're like that's a mistake right. Let's talk about like why that's inappropriate in this space and then like what we need you to do moving forward so that whatever the end goal is right which is usually student achievement. Like if anything. Our job is to empower these kids. And so we want to make sure they learn like different ways to behave in certain spaces so that when they do get to the table like people are impressed by them. Right. And people are not like oh this kid like doesn't give eye contact like we don't. They don't speak up. Right. These are things that when you go in interviews when you have first impressions with people they look at those things and they judge you immediately.

MAX: At Excellence Girls, like a lot of charter schools, there’s a big focus on college. This first grade classroom I visited was named after Spelman, the historically Black women’s college in Atlanta.

TEACHER: Good morning Spelman.

STUDENTS: Good morning Miss [unintelligible]. Good morning Miss Walker. Good morning Miss [unintelligible].

TEACHER: Happy Friday.

STUDENTS: Happy Friday.

TEACHER AND STUDENTS: It’s Friday it’s Friday it’s the end of the year it’s the last day whatcha gonna doooo?

MAX: They do have some of the behavioral rituals that are often identified with “No Excuses” schools. But they try to make it fun.

TEACHER: Spelman College! Who! Are! You!

STUDENTS: Don’t you wish you were a Spelman girl like usssss. Achieving all my dreams by myself take a look ayyy. I’m a hard worker I’m a book learner I’m in first grade but I’m still a go-getter. Yeah I love who I am. Tssss. Spelman got the school hot, super hot. Hot like fiyaaah.

MARK: If you didn’t recognize it, that was “Nonstop” by Drake… revised just a bit.

MAX: So that’s super cute, right? So it’s hard for me as an observer to square what I saw with how people feel about these schools, which is that they’re putting their neighbors out of business.

MARK: Charter schools are growing and traditional public schools are shrinking across District 16. Is this a zero-sum game? After the break.

MIDROLL BREAK

ANTHONINE PIERRE: Hi, this is Anthonine Pierre from the Brooklyn Movement Center. Thanks to those of you who came out to the discussion group we hosted last month! We’ve got a couple more ways for you to get an inside look at the podcast.

ANTHONINE: Mark hosts Brooklyn Deep’s other podcast, Third Rail, every month, but this month I’m in the hosting chair to interview him & Max about what it’s been like making School Colors. It was a great conversation and if you subscribe to Third Rail now, you can get the episode immediately when it drops next week!

ANTHONINE: Next, if you’re in New York, Mark and Max will be speaking at the monthly meeting of the Alliance for School Integration and Desegregation, also known as ASID. That’s at 6pm on Thursday night, November 21st, at P.S. 44 Marcus Garvey in Bed-Stuy. We’ll put a link to RSVP in the show notes. Alright, on with the show!

COMPETITION

MAX: Last year, District 16 had 19 traditional public schools and 8 public charter schools serving elementary and middle school students within its borders. And there were almost as many students in these 8 charter schools as there were in the 19 traditional public schools combined. It’s worth pointing out that not all those charter school students are being siphoned off from District 16 -- a lot of kids who live in District 16 are leaving to go to traditional public schools in other districts, and a lot of kids who go to charter schools in District 16 are coming in from elsewhere.

MARK: Nevertheless, the way that defenders of the district see it, there’s a cycle: charters move into the district, students leave the district for the charters, enrollment goes down, leaving more space for more charters to move in, and on and on and on. So yeah, it can feel like a zero sum game: anything you get, I lose.

OMA HOLLOWAY: You know as somebody once told me you know they'd rather be in a room with Palestinians and Israelites than to be in a room with diehard charter school and traditional public school parents who sometimes stay very entrenched on their sides.

MARK: Oma Holloway has worked in youth programming in Central Brooklyn for 25 years. But when her daughter Athena was about to hit kindergarten, she wasn’t sure where she wanted her to go to school.

MAX: In most of New York City’s 32 school districts, each elementary and middle school has a zone. If you live in that zone, you are legally entitled to a seat in that school - that’s your “zoned school.”

OMA HOLLOWAY: And I went to my zoned school which is actually right across the street from where I live and I was not impressed. I was not impressed at all. It was like This is my only option for you know. And that was the messaging that kept coming back to me. The message was you know you go to your zoned school if you think it's a quality school or not just because it's there we have to support it. We may have to support a school that you don't believe the leadership or the teachers are providing the best for your children.

MARK: And when she went to visit a couple of charter schools in her neighborhood, she liked what she saw.

OMA HOLLOWAY: I was working full time. I'm a single parent so to have the opportunity to have you know programming from you know early in the morning to after school programming. I was always impressed with the parent engagement. And I just didn’t get that in my zoned school at the time.

MARK: Oma not only enrolled in a charter school -- actually, she’s been through a couple of them, including Ember -- she became a local advocate for charter schools.

MAX: She also chairs the Youth & Education Committee on the Community Board for Bedford-Stuyvesant, though she says she works hard to separate that from her charter school advocacy.

MARK: But at the end of the day, she believes that parents, especially parents of color, deserve to have options besides their zoned school.

OMA HOLLOWAY: Schools that meet the needs or the learning styles um of their child um without having the price tag of a private school that's like you know can be thirty thousand dollars or so. I would like to have that option and so I strongly believe in having charter schools.

MAX: It’s hard to dispute that parents deserve to have options. But because most charter schools share a building with a traditional public school, they seem to be in direct competition for space, resources, and kids.

MARK: And a lot of people feel like that competition is rigged. Some charter schools get a lot of outside money, some don’t -- but because they’re independent of the central bureaucracy and union contracts, they all have greater flexibility with how they spend their money. And many spend that money on renovations and technology.

RAFIQ KALAM ID-DIN: What you hear from people is like ah you know in the same building you have the same kids but they have these two different experiences they have this nice beautiful environment on one floor and this broke down environment on another. To me that just highlights the pervasive inequity but it doesn't say to me that we need to strip the kids who have not had anything for a long time ever of what they're getting what their benefit is.

NEQUAN MCLEAN: Some parents like shiny things.

MARK: NeQuan McLean, president of the Community Education Council for District 16.

NEQUAN MCLEAN: And if you can show them something shiny. That's the way they're going to go. But just because it's shiny doesn't mean it's the best fit for your child.

MAX: Many charter schools also spend money on student recruitment. (They have to, since no one’s automatically enrolled in a charter school like they might be in their zoned school.) But that’s created pressure on traditional public schools to keep up.

RAHESHA AMON: It was not a fair game.

MARK: When Rahesha Amon became the superintendent of District 16, she realized that in addition to serving as the educational leader for the district, she’d have to be chief marketing officer, too.

RAHESHA AMON: When you and I went to school what principal had to recruit.

MARK WINSTON GRIFFITH: Right no. I know.

RAHESHA AMON: I mean what principal had to market brand you know those are not even terms that are natural to an educator. It's like saying to a plumber now come fix my lights. You know like what. I would not want my plumber. He is great. To do anything with my lights. Right. So now you've told educators right. Who. That is an enormous task in itself. Well you know what. While you're building the future of our country and society now figure out how to attract families to come.

MAX: Like… I understand what she’s saying and I’m sympathetic but it’s been 15 years that we’ve had school choice. Why haven’t district schools learned to compete?

MARK: Nowhere in the history of the system has there been any kind of culture of self-promotion and marketing that I know of. I just don’t think they think about schools that way. It’s a passive system.

MAX: Well, that inertia puts them at a disadvantage compared especially to a big charter school network, with central staff who are devoted to marketing.

MARK: But the best marketing is performance. On average, across the country, charter schools seem to be doing about the same as traditional public schools on standardized tests. But according to the New York City Charter School Center, Black students in charter schools here score proficient in English and Math at twice the rate of Black students in traditional public schools.

MAX: Yeah, that’s a pretty striking statistic, But defenders of traditional public schools say that even those test scores are rigged, because of “selection bias”: even though charter schools admit students by a random lottery, only the most motivated parents, people like Anika Greenidge, will sign up for a lottery in the first place, and their kids are more likely to do well anywhere.

MARK: And some argue the selection bias in test scores is not just an inevitable function of who’s signing up for these schools, but that it’s deliberate -- that charter schools, especially of the “No Excuses” variety, find ways to push out students (and parents) who can’t rock with the school’s way of doing things.

MAX: Odolph Wright is the Parent Coordinator at P.S. 5, a traditional public school in District 16. Year after year, he has seen some of his brightest students leave for charter schools nearby.

ODOLPH WRIGHT: People don't know value. They know charter schools. Supposed to be better and a number of them not many but number of them come back and they come back after the fact. Which means after October 31st. That school got the money. They come back. We don't get the money. [laughs]

MAX: Let me explain why the timing is so important: school funding is based on enrollment, and enrollment is fixed for the entire year at whatever number of students you have on October 31st. So after October 31st, even if you get more students, you don’t get additional funds.

ODOLPH WRIGHT: I don't know if they release them. I don't know if they. But they come back after that time period and you know we got the kid. But we don't get the money.

MARK: That’s a pretty serious charge: that charter schools are waiting until November to push out students, so that they get to keep the money that comes with them, but don’t have to risk these kids bringing down their test scores.

MAX: Yeah. Is this kind of thing happening systematically? I don’t know.

MARK: Either way, people believe it. People believe there is a conspiracy to do these schools dirty. Which goes a long way to explain why this conversation is just so toxic.

ACCOUNTABILITY

MAX: And this is exactly the kind of thing that makes NeQuan McLean, president of the Community Education Council for District 16, want to have more oversight of the charter schools in his district.

NEQUAN MCLEAN: Charter schools are not accountable to us to a certain point. Which we believe they should be. They're in our community. They're educating our children. We should have some say in what the processes are.

MARK: The CEC hardly has any power over traditional public schools; but absolutely none over charter schools, even those in the same building. So NeQuan, at least, can’t do anything to make sure that charter schools are taking in their fair share of students with the highest need: students with disabilities, English language learners, and students in temporary housing.

RAFIQ KALAM ID-DIN: I would actually say that charter schools are the most accountable public schools that there are in the state without question.

OMA HOLLOWAY: If they fail they can be closed down. And closed down fairly quickly. And and I think that people don't want to pay attention to that. That you know. It is very hard for charter schools stay open for 10 years if they have a failing record. It's just that they're not gonna allow that to happen in this city where we've seen failing schools that were on the list for a long time and they were allowed to stay open for a long time which is failing our kids.

MAX: Nationally, lack of oversight is one of the most common criticisms of charter schools. For-profit corporations are allowed to basically run amok in the charter school sector in states like Michigan. Charter schools in New York are more accountable than in many other places, but they’re accountable to the state education department, not to this community. Which is kind of a knock against Rafiq’s notion that charters can be a vehicle for self-determination in the mold of Ocean Hill-Brownsville.

PHILANTHROPY

MARK: Another knock is the role of philanthropy. Not all, but many charter schools are backed up by big money from the financial industry and corporate foundations -- including major players like the Walton Foundation, aka Wal Mart money.

MAX: Rafiq Kalam Id-Din doesn’t see how this is a problem. He says he doesn’t get big philanthropy but he would take it if it was offered.

RAFIQ KALAM ID-DIN: You have charter schools that come along and you have amazing philanthropy that's giving on behalf of poor black and brown kids. And it's interesting to say that that exacerbates the inequity. I would say absolutely not.

MARK: I mean… you could also argue that philanthropists and foundations are putting money into charter operators with one hand and withholding money from public education with the other by advocating for lower taxes.

MAX: And this money doesn’t always go to individual charter schools or even charter school networks. Charter schools have been a lobbying powerhouse, with millions of dollars poured into advocacy groups and thousands of charter school parents and children regularly put on buses up to the state capital to show their strength.

MARK: So, you have to ask yourself, why are these rich people so interested in what’s happening in these neighborhood schools?

MAX: Even though he defends the role of philanthropy in the spread of charter schools, Rafiq also believes it’s because of philanthropy that “No Excuses” has been so predominant.

RAFIQ KALAM ID-DIN: White philanthropists white organizations white individuals invest with people who look like them even in this thing that they care about. And I'll ask them the question. Do you think that our kids are entitled to the same kind of private school education that many of their children can afford and get. In those schools. No one's walking around in a particular way. No one cares about how they sit. They’re giving them the freedom to think in a follow their curiosity to build themselves up in their identity. So that's what we do here. We think our children deserve that. Because if you look at it. Those are the people go on to run our economy. Right. And if people go to traditional public schools are not. They are the cogs.

MARK: So what makes a public school public? Is it where the money comes from? Is it who calls the shots?

MAX: Charter schools are publicly funded, even if they supplement that funding. And to be fair, traditional public schools also supplement their budgets with private money, in the form of PTA fundraising.

MARK: And some traditional public schools raise a lot of fricking money, too.

MAX: Right. When there are public schools in New York City with a million dollar PTA, who are we to say that some hedge fund guy on the board of a charter school isn’t just evening the score?

MARK: Traditional public schools can also apply for foundation grants. And Odolph Wright, Parent Coordinator at P.S. 5, told us that his school is pretty good at getting grants, even though they have to do everything themselves.

ODOLPH WRIGHT: We are technology overflowing in this school. And most of stuff we get the laptops the computers the programs all the music. We have a music program here and all these things we get because of grants but those grants don't cover salaries. Beautiful lab. Fantastic lab. Over abundance lab. Ah. My goodness. Think about it. But we don't have a teacher. We have more students we can hire a teacher.

MORATORIUM

MAX: But like almost every other school in District 16, enrollment at P.S. 5 has kept dropping. So when Rahesha Amon came on as superintendent in early 2016, NeQuan and the CEC asked the Department of Education for a two-year moratorium on the siting of new charter schools in the district.

MARK: The idea was: give the new leader some time, give her the opportunity to see what she was working with and try to make progress on enrollment without having to worry about the looming threat of new charter schools.

MAX: Much to a lot of people’s surprise, Charter school advocate Oma Holloway supported the CEC’s call for a moratorium.

OMA HOLLOWAY: You know people were like you're a charter school advocate how could you How could you defend that and I go. Why not. Maybe it is too many. It's too many for the charter schools the charter schools don't want another charter school in the community because they they're fighting and that's the funny part. The irony is the charter schools were feeling the exact same way as the traditional schools they did not want any more charter schools in the neighborhood could was competing with their numbers.

MARK: The Department of Education never officially responded to the CEC’s request for a moratorium, but they appeared to act on it: there were no new charter schools sited in District 16 for two years.

MAX: Now this was supposed to be an opportunity for the district to try to reverse course: to improve schools and improve marketing.

NEQUAN MCLEAN: We have schools that are doing great work. So what we're trying to now do is re rebrand our schools so that we're promoting them the right way because we do have great things that's going on but I believe people don't know about them.

MAX: But it’s been a struggle to get principals on board.

RAHESHA AMON: So I get it like I get it it's tough I get it. No one told you in education 101 you'd be doing this but when the music changes so has your dance got to change. The music has changed. We've got to dance differently.

MAX: But as we discussed in the last episode, even if a school leader doesn’t get with the program, doesn’t learn to dance differently, there’s not much district leadership can do.

RAHESHA AMON: Charter schools aren't going anywhere as far as I see so I think we have to I mean that was part of my wanting to work with the charter schools and building the bridge and relationships. We we have to work with one another.

MAX: To that end, she established something called the District-Charter Collaborative, which both Ember and Excellence Girls have been a part of, visiting and learning with district schools.

MARK: But after two years of the unofficial moratorium, the trend line hadn’t changed. Enrollment kept going up in the charter schools and down in the district schools. NeQuan kept asking the central DOE to put a marketing person on staff for the district, but no dice. And in late 2017, as those two years were about to be up, the DOE announced a new siting of a charter school in District 16. Right on schedule.

MAX: The November CEC meeting that year was an especially tense one. After more than an hour of discussion about the previous year’s test scores -- which were not encouraging -- they moved on to the subject of this new charter school that had been proposed for the district. Someone in the audience asked NeQuan, “Why don’t you leave the schools alone?” as if he was the one bringing charters in. This is more than 2 hours into the meeting; you can hear how tired he is.

NEQUAN MCLEAN: And I'm going to be very honest with you. I'm going to be very honest with you. Parents are choosing charter schools. Parents if parents were not choosing charter schools there would be none in this district. So parents are choosing them. What we have asked as a Council and you all correct me if I'm wrong is that we want to be able to place them. We don't want them to affect the schools that are doing well. And I'm gonna be honest. I. When we first started we were fighting charter school. We felt like we had too many. The charter schools feel like there's too many like. But the other week I was at it the other week I went to a hearing and I literally left from the hearing crying and was going to give up because I said what am I doing. Why am I leaving my kids at home to go fight for something that the principals the teachers and the parents from that school didn't even come out to say yay or nay. Even the charter school. No parents came from that school. So I was like oh I'm done with this. We can't continue to fight for something that other people are not fighting for. We can't continue to fight for grades like this. If the people the parents in those schools are not speaking up about those grades.

MAX: That was almost two years ago. The last time we checked in with him, over the summer, I reminded him of this speech he’d given.

NEQUAN MCLEAN: You know what I've learned since then is that I think. Families feel like it's going to happen anyway. So why fight it. And that's what we're trying to change.

MAX FREEDMAN: if the culture is that people feel like they can't they can't really I haven't you have any effect on anything how do you change that culture.

NEQUAN MCLEAN: We show them. We show them that change happen.

CHANGE

MARK: And change is happening.

MAX: For years, charter schools enjoyed bipartisan support -- no less than President Obama incentivized states to allow for more charter school expansion. But as the political winds in the Democratic party seem to be turning left on many issues, nationally and locally, charter skepticism is on the rise.

MARK: After the 2018 election, the New York state legislature became united under Democratic Party control for the first time in nearly a decade. NeQuan McLean seized the moment.

MAX: NeQuan went up to the state capital in Albany several times to lobby elected officials to change the regulations governing Community Education Councils: from now on, thanks in part to him, the CECs will be authorized to say yes or no to a charter school placement.

MARK: The city can still go against what the CEC recommends, but if they do, they have to say why in writing. (Alright, maybe that doesn’t sound like much, but it’s something.)

MAX: By law, New York State has a cap on new charter schools. Every year like clockwork, the state legislature has lifted the cap. But not this year.

MARK: This year, after lobbying from NeQuan and others, Albany declined to lift the cap, meaning no new charter schools for the time being.

MAX: At the same time, Ember was preparing to graduate its first class of eighth graders, and they applied to expand to the high school grades.

MARK: And despite the charter cap, they should have been fine; this was an expansion, not a new charter. But when we caught up with Rafiq in May, their plans had hit a bump in the road.

RAFIQ KALAM ID-DIN: So right now our current school is caught up in getting our high school approved. No reason. City's approved us. But the state and I think because the state doesn't believe in our approach to education the state is blocking it right now.

MAX: He says the state has never really believed in Ember’s approach to education. Always complained that they don’t do test prep. Always questioned their curriculum.

RAFIQ KALAM ID-DIN: We're the only school in this position right. Out of all the schools that have come up is it the only like culturally responsive Afro centered school that you have a question about whether or not there is community support for this model. Even the fact that this is even a question this is a question that only applies to our school. No other school. No other charter school. I mean it’s because all the other charter schools that they viewed are white led charter schools. No one else has had to deal with this but we do.

RAFIQ KALAM ID-DIN: We'll see. We'll see whether or not we get some movement here. But the fact that we're at the end of May right. This is supposed to have happened months ago. Our application's been in since the beginning of November. And our students because of course because the city was like yeah of course we're going to approve you all. All of our students turned down their high school acceptance because they want to stay with us.

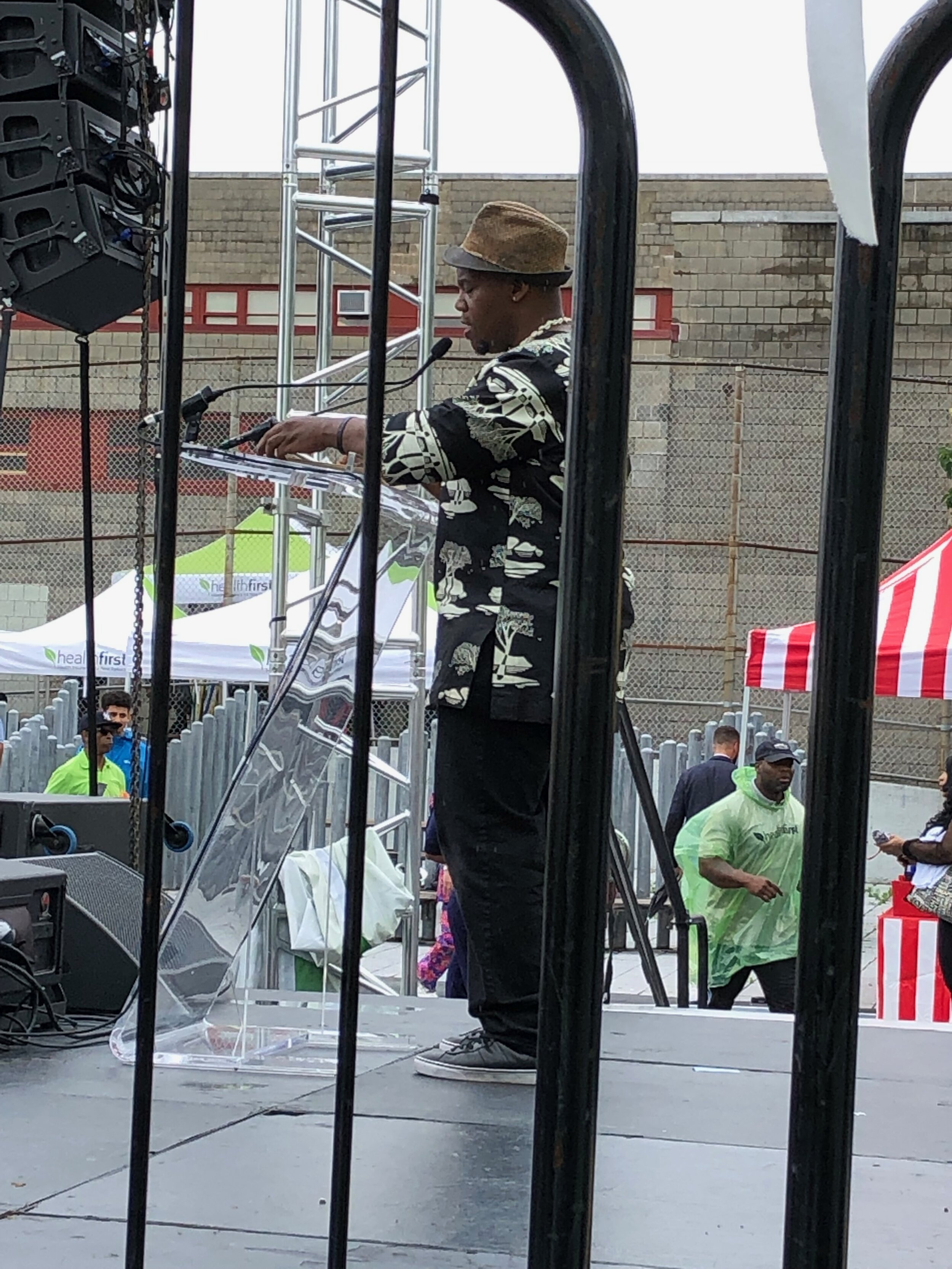

MARK: If you know Rafiq, you know he has played the politics around here better than most, and he worked his connections to get elected officials to speak out on his behalf. He also brought a group of his students up to the state capital in Albany to protest.

MAX: But the Regents were not moved. In June, they voted to deny Ember’s high school expansion.

MARK: One reason given by the Regents was a “lack of community support” -- and they specifically mentioned the Community Education Council.

MAX: And the CEC for District 16 did send a letter to the State Board of Regents expressing their opposition.

MARK: So we wondered if this means that the state is now, suddenly, actually listening to what the CEC has to say. So we asked NeQuan, president of the CEC, if he thinks that’s the case.

MAX: NeQuan said he’s happy about this decision. He says it should have been made because of the CEC’s letter. He believes the CEC’s opinion should hold that much weight. But he doesn’t believe they do. Because if they did… The thing is, Ember was not the only charter in District 16 with a revision or expansion before the Board of Regents last year. The CEC wrote a letter opposing each one of them. And only Ember’s was denied.

MARK: “They do what they want when they want to do it,” he said.

RAFIQ KALAM ID-DIN: I think it comes back to this core idea about who believes what's best for our community. Is it us the people who live here who are part of it or people who are up in Albany.

MARK: NeQuan and Rafiq are agreed on one thing: Albany should stay out of it. But who exactly is the “us” that Rafiq is referring to? Who represents this community? Who is the true torch-bearer for community control?

MAX: I don’t know. But at the end of the day, Ember doesn’t have a high school. (At least not yet.) And their first graduating class of 8th graders have had to find other places to go.

MARK: So there was some sadness tempering the joy, when Rafiq spoke at their graduation ceremony in June.

RAFIQ KALAM ID-DIN: You know we live in difficult and challenging times and as we look out into the world we are sending you all into. I apologize that I was not able to deliver the high school for you. I really believe that we have prepared you for this world. And I wish we had more time. But we have you. We have you. You are going to go out into this world and set it on fire. And in its place you are going to build a place of justice and equity unlike anything we have seen before. That is you.

RAFIQ KALAM ID-DIN: Before we end. We've got a bit of our call and response that we're going to leave on. We begin with an affirmation as we always do. Before our students brothers and sisters if I say amandla you say. If I say maribuye. I love myself. I love my hair. I love my ears. I love my eyes. I love my nose. I love my lips. I love my skin. I love my brain. I love myself. And I love you. Congratulations Class of 2019. Everybody welcome to the community cookout. Enjoy yourself. Have a great day. Thank you.

MAX: Charter schools can’t take all the blame for the under-enrollment of District 16. That’s because there really are fewer and fewer children here. Thanks to gentrification, which brings not only $4 coffee and higher rents, but a lot of young people without kids, like me.

MARK: And until recently, most of the white, middle class folks moving to Bed-Stuy who do have kids have not been sending them to local schools. But that’s starting to change — for better or worse.

FELICIA ALEXANDER: You're not born and raised here. You're not do or die. You just came here because it's the popular destination.

NEQUAN MCLEAN: They went into a church started a choir. And did not speak to the pastor.

TANYA BRYANT: You took my home and now you want my school too.

VIRGINIA POUNDSTONE: And I was like Yo no no.

NATASHA SEATON: Oh this is racism. Damn.

SHAILA DEWAN: How did I get to a place where I was trying to help. And I became public enemy number one. How did this happen.

MARK: District 16 confronts gentrification and the future. Next time. On School Colors.

CREDITS

MARK: School Colors is written and produced by Mark Winston Griffith and Max Freedman. Edited by Max Freedman and Elyse Blennerhassett. Engineering, mixing, and sound design by Elyse Blennerhassett.

MAX: Production support from Jaya Sundaresh and Ilana Levinson. Music in this episode by avery r. young and de deacon board, Chris Zabriskie, Blue Dot Sessions, and Ricardo Lemvo.

MARK: Special thanks to the students and faculty of Ember and Excellence Girls, Mesha Byrd, Natasha Capers, Nicole Cirino, Lena Gates, and Barbara Martinez.

MAX: School Colors is made possible by support from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, and the NYU Metropolitan Center for Research on Equity and the Transformation of Schools.

MARK: School Colors is a production of Brooklyn Deep, the citizen journalism project of the Brooklyn Movement Center, a black-led community organizing group in Bed-Stuy. More information at brooklynmovementcenter.org.

MAX: Visit schoolcolorspodcast.com for more information about this episode, including a full transcript. Follow us on Twitter and Instagram @BklynDeep.

MARK: You can help spread the word about School Colors by leaving a rating and review on Apple Podcasts, sharing on social media, or telling a friend.

MAX: And like Anthonine said, you can come meet us in person at the upcoming meeting of the Alliance for School Integration and Desegregation. That’s on Thursday night, November 21st, at P.S. 44 Marcus Garvey. We hope to see you there. Until then --

MARK: Peace.