Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn is one of the most iconic historically Black neighborhoods in the United States. But Bed-Stuy is changing. Fifty years ago, schools in Bed-Stuy's District 16 were so overcrowded that students went to school in shifts. Today, they're half-empty. Why?

In trying to answer that question, we discovered that the biggest, oldest questions we have as a country about race, class, and power have been tested in the schools of Central Brooklyn for as long as there have been Black children here. And that's a long, long time.

In this episode, we visit the site of a free Black settlement in Brooklyn founded in 1838; speak to one of the first Black principals in New York City; and find out why half a million students mobilized in support of school integration couldn’t force the Board of Education to produce a citywide plan.

CREDITS

Producers / Hosts: Mark Winston Griffith and Max Freedman

Editing & Sound Design: Elyse Blennerhassett

Original Music: avery r. young

Production Associate: Jaya Sundaresh

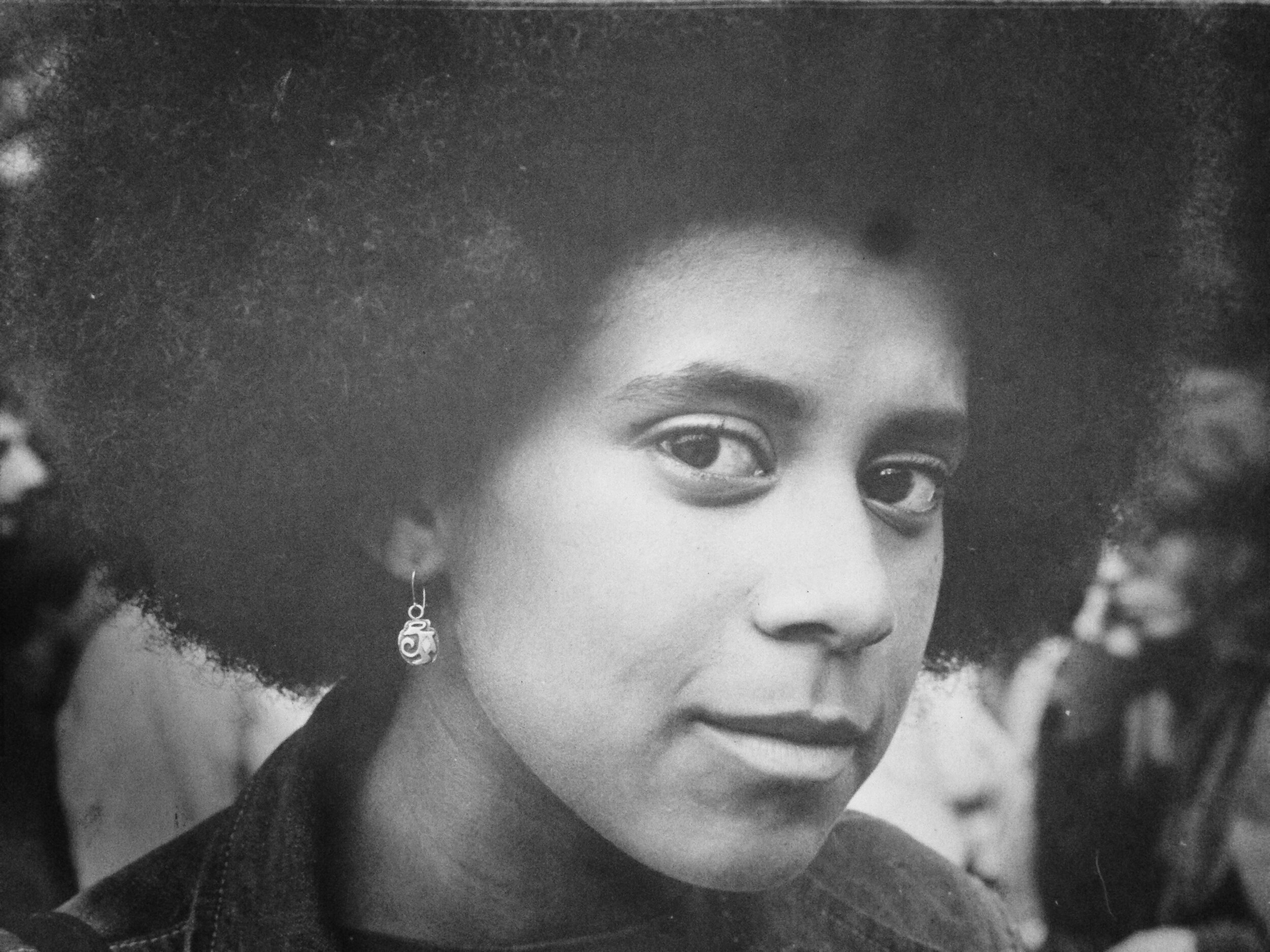

Featured in this episode: Kamality Guzman, Sarah Johansen, Cieanne Everett, Alphonse Fabien, Julia Keiser, Dr. Adelaide Sanford, Rev. Milton Galamison, Monifa Edwards. Photo credit: Weeksville Heritage Center.

School Colors is a production of Brooklyn Deep, the citizen journalism project of the Brooklyn Movement Center. Made possible by support from the NYU Metropolitan Center for Research on Equity and the Transformation of Schools and the Carnegie Corporation of New York.

IMAGE GALLERY

REFERENCES

Mapping Inequality: Redlining in New Deal America (University of Richmond)

Brooklyn’s Promised Land: The Free Black Community of Weeksville, New York (Judith Wellman, 2014)

Battle for Bed-Stuy: The Long War on Poverty in New York City (Michael Woodsworth, 2016)

Why Busing Failed: Race, Media, and the National Resistance to School Desegregation (Matthew Delmont, 2015)

TRANSCRIPT

OPENING

MARK WINSTON GRIFFITH: Marcus Garvey is widely considered the founding father of Black nationalism.

Born in Jamaica, where my own family is from, Garvey opened the first U.S. branch of his United Negro Improvement Association in Harlem in 1917, and by 1920, the UNIA had chapters in more than 40 countries around the world.

They established the Negro Factories Corporation, the Black Cross (modeled on the Red Cross), the Negro World weekly newspaper, and the Black Star shipping line. If you’ve ever seen the red black and green Black liberation flag, that comes from the UNIA.

Marcus Garvey died in 1940, but his ideas lived on. From Oakland to Omaha to Brooklyn, generations of Black Americans were inspired by Garvey to build Black businesses and institutions.

In Brooklyn, nowhere did this ideal of Black self-determination come more alive than in Bedford-Stuyvesant. So it’s no surprise that in 1987, a major thoroughfare in Bed-Stuy was renamed Marcus Garvey Boulevard.

But Bed-Stuy is changing. And you can see that change very clearly, but in very different ways, at two different public schools that both happen to sit on Marcus Garvey Boulevard.

MAX FREEDMAN: At the corner of Marcus Garvey and Lafayette, right across the street from the place where I do my laundry - there’s a public elementary school called P.S. 25. The New York City Department of Education says that P.S. 25’s four-story brick building has room for almost a thousand students. Last year, there were just 82.

So on a cold Monday night in February 2018, I went to P.S. 25 for a public hearing. There might have been 30 people there, scattered around an auditorium that seats two to three hundred. Before the hearing began, a few kids with handwritten signs just about as tall as they were, started marching up and down the aisles.

P.S. 25 STUDENTS: Save our school! Save our school! Save our school!

PHIL WEINBERG: The NYC DOE is proposing the closure of P.S. 25 based on its persistently low enrollment and lack of demand from students and families in the neighborhood. Consequently the DOE is proposing that P.S. 25 close at the end of the school year.

KAMALITY GUZMAN: This school is just it's it’s small to them. It’s big to us but it's small to everyone else. There’s only a few children in the school so they don't think it's that serious or just you know just close down the school there's only a couple of children in school but. You know we see the same people over and over you know you just grow accustomed to it. They know what your kids need. They know what they lack. It's just it would be sad to close it.

MAX FREEDMAN: And what did you think of this meeting tonight.

KAMALITY GUZMAN: I think it’s it’s not going to make a difference what we say. Their mind is made and whatever happens it don't matter what we think.

MAX: P.S. 25 is a part of Community School District 16, which covers about half of Bed-Stuy. District 16 has a higher percentage of Black teachers than any other district in the city. The superintendent is Black. Almost all of the principals are Black. Most of the schools are named after Black heroes. And like P.S. 25, almost every school in the district is hemorrhaging kids.

MARK: But just three blocks down Marcus Garvey Boulevard, I found a very different scene: another public school, also in District 16, that appeared to be in high demand: Brighter Choice Community School.

A couple of months after that hearing at P.S. 25, I went to Brighter Choice for an open house. The gym was alive with music and games, laughing children and wide-eyed parents. Most of the parents were Black - in fact I knew quite a few of them already - but there was a handful of white parents as well.

SARAH JOHANSEN: My name is Sarah Johansen and I'm here with my husband Rogan and my son Praben and we are here because we applied to the school for next year so hopefully he'll get in in September.

MARK: Sarah is originally from Denmark.

SARAH JOHANSEN: And it's always been really important to us that he went to a place that was close to where we live and that was certainly in the district that we live in. We don't want to send him somewhere else. And plus you know the school is great so we’re just hoping that he gets in here.

CIEANNE EVERETT: Well I mean it’s really good that. I'm really proud that the school is very popular. I'm really proud that people are looking and vying for spots like people are literally vying to get their kids in here. And that's amazing.

MARK: Cieanne Everett was the PTA secretary at Brighter Choice at the time. And she was excited that other parents were excited about the school… with some reservations.

CIEANNE EVERETT: I really hope people who are vying for the school who are coming and wanting their children to be here. I'm really hoping they're coming with the notion of wanting to be a part of a community.

MARK: So why would parents be throwing elbows to enroll their children at Brighter Choice, when the schools all around them are desperate for students? And if Brighter Choice is doing so well, what is Cieanne Everett so worried about?

CIEANNE EVERETT: You know change is good but we we want people to come in. You fell in love with the school for a reason. Come and just meld into that reason. Come and be a part of the reason. We don't need we don't need the change makers right now.

MARK: You’re listening to School Colors, a podcast from Brooklyn Deep about how race, class, and power shape American cities and schools.

My name is Mark Winston Griffith. I’m an organizer, a journalist, and a public school parent; I was born in Central Brooklyn and I’ve been working here for 35 years.

MAX: My name is Max Freedman. I’m a teacher, an audio producer… and a gentrifier.

MARK: Together, we’ve been to dozens of public meetings and interviewed more than 60 people:

MAX: Parents, teachers, and administrators;

MARK: Politicians, historians, and activists;

MAX: My landlord;

MARK: My uncle;

MAX: Trying to figure out what’s going on here and what it means. We started with what seemed like a pretty straightforward question: Why is enrollment going down in District 16?

MARK: But nothing here is straightforward.

MAX: You could blame it on the quality of the schools themselves.

FELICIA ALEXANDER: I have a big issue with people constantly saying District 16 schools suck they suck they suck. No they don't.

MARK: You could blame it on the competition from well-funded charter schools.

NEQUAN MCLEAN: Some parents like shiny things. And if you can show them something shiny. That's the way they're going to go.

MAX: You could blame it on gentrification. Bed-Stuy is changing, and a lot of the people moving in either don’t have kids (like me) or send their kids elsewhere.

FARAJI HANNAH-JONES: The thought of even considering a public school in this neighborhood in our neighborhood was unheard of. You know no one would ever think about doing anything like that.

MARK: Ironically, if more parents like Sarah Johansen are convinced to choose their local school, gentrification might actually resurrect the district.

MAX: Which would also contribute to the racial and economic integration of at least one corner of New York City’s deeply segregated school system.

MARK: But in Bedford-Stuyvesant — one of the most iconic historically Black neighborhoods in the United States — integration riding on the coattails of gentrification might be a tough sell. Some see it as part of an erasure of Black and low-income people.

FELICIA ALEXANDER: I think that every time minorities have something good it gets taken away from us. And I'd like to be able to hold on to something.

MAX: District 16 is at a tipping point. And what’s at stake is a lot more than lines on a map. It’s the power to control not only how and what children learn, but what kind of city we’re going to live in and who that city is going to serve.

MARK: And the biggest, oldest questions we have as a country about power have been tested and worked out, right here in the schools of Central Brooklyn for as long as there have been Black children here. And that’s a long ass time.

DOLORES TORRES: The plan for community control was.

REV. C. HERBERT OLIVER: We knew that Black people were capable of running schools.

ALBERT SHANKER: They will burn the city down.

CHARLES ISAACS: It was a beautiful thing that got destroyed.

SEGUN SHABAKA: The government was hostile.

CLEASTER COTTON: The pressure that we went through as children killed many of us.

RAFIQ KALAM ID-DIN: This is what happens when you don't have people who you're trying to serve as a part of the solution.

DAISY GRIFFEN: They want us to be like puppets with our heads down when they say to do stuff but we not having it.

NEQUAN MCLEAN: What am I doing. Why am I leaving my kids at home to go and fight for something that the parents from that school didn't even come out to say yea or nay.

FELICIA ALEXANDER: You’re not born and raised here. You’re not Do or Die. You just got here.

VIRGINIA POUNDSTONE: I am white but I am no dummy.

ANIKA GREENIDGE: Who the fuck do you think you are?

SHAILA DEWAN: I am a pariah.

MARK: What’s happening in District 16 is happening across New York City. And what’s happening in New York City is happening in cities across the country.

MAX: We’ve got eight episodes to tell you all about it.

MARK: Welcome to School Colors.

INTRODUCTIONS

MARK: Before we really get started, I want to tell you a little more about who we are, where we are, and why we’re doing this.

MAX: If each borough of New York were its own city, Brooklyn would be the third largest city in the United States, after L.A. and Chicago.

MARK: And at its center is the largest urban concentration of Black people in the country.

Exactly which neighborhoods make up the area we call Central Brooklyn can be debated, but the historic core of it is Bedford-Stuyvesant and Crown Heights. And my roots here run deep.

My grandmother and her siblings, born in Jamaica, first came to Crown Heights in the 40s and 50s. I was born here, my parents moved us to Queens when I was still in elementary school, but I made a very conscious effort to return after college, in 1985.

At the time, mainstream America saw it as a ghetto, but I always saw the beauty, the strength, the grit. To walk blocks and blocks and see nothing but Black people celebrating themselves, to see their culture, to eat their food, to patronize their businesses. That was everything to me.

So that’s why I wanted to fight for this place. I’ve started and run half a dozen community organizations, worked for elected officials and have even run for office here myself. In 2011, I co-founded the Brooklyn Movement Center, a Black-led community organizing group. We fight discriminatory policing, organize tenants to push back against abusive landlords, and we’re even building a neighborhood owned food coop. But it’s really just our way of surviving gentrification, cuz it feels like we as Black folks are an endangered species.

I get it. People see the brownstones, the tree lined blocks, the profound sense of history and community, and they want a part of it. People see the value here. But for many, that value is predicated on getting rid of the low-income Black people who are inconveniently still around. Bed-Stuy is now less than 50% Black. So what I’ve always seen as so beautiful, it’s evaporating.

MAX: My roots here run deep, too.

My grandfather came here with his family in the 1920s. They were Jewish immigrants from what’s now Ukraine and they landed in Brownsville, just southeast of Bed-Stuy. My mom was actually born in the area, but my grandfather and his brothers and sisters, they all got out of “the old neighborhood” and never looked back. So I didn’t even know that I had family history here in Brooklyn until I got here as an adult.

You know Mark, it’s funny: one thing we have in common is that we both moved here right after college. But it wasn’t such a conscious decision for me. To be honest, I only really came to Bed-Stuy because I got priced out of the neighborhood next door.

But once I arrived, everything that you’re describing is what I saw. The brownstones and the tree-lined blocks and the pride… I saw how what made the neighborhood beautiful and unique was being celebrated and erased at the same time. And I understood that I was a part of that, and I understood that it was much bigger than me.

I’ve been here for seven years now. Teaching New York City history in public school classrooms all over the city. Using theater to organize against discrimination in housing and health care. Eventually, I decided to go to grad school for urban design, and I knew from the beginning I wanted to use that experience to learn more about this place where I live but also to contribute something to the fight that you’ve been fighting your whole life.

Having been both a gentrifier and a teacher, I was especially interested in the relationship between gentrification and schools, and I saw on the website of the Brooklyn Movement Center that you were doing some parent organizing, so… that’s what brought me to you.

MARK: And we had done some research on District 16 at BMC a few years before you showed up, but our work had been basically either ignored or blocked by anyone who had the ability to do anything with it … which is a story we’ll get to later.

MAX: Anyway, I wrote my thesis, and when I was done we were both like, okay, I think we need to put this out into the world. And that’s how this podcast was born.

MARK: We felt like we had stumbled upon something, this rich and complicated and unique moment in the history of this neighborhood and city that we wanted to capture and share in real time.

MAX: And the more we learned, the more we knew that we’d have to go back in time, way back in time, to fully understand what’s happening now.

MARK: Alright, should we go to Weeksville?

WEEKSVILLE

ALPHONSE FABIEN: So a lot of people who I meet especially those who live in Brooklyn they say oh I never heard of this. I think people for some reason are like surprised when they hear that there was a free Black settlement right here in Brooklyn.

ALPHONSE FABIEN: My name is Alphonse Fabien. I am a tour educator at the Weeksville Heritage Center.

MARK: The Weeksville Heritage Center teaches the history of Weeksville: a free Black settlement founded in Central Brooklyn almost 200 years ago.

MAX: Let’s back up a second. The first Africans arrived in New York -- or, as it was known at the time, New Amsterdam -- as the property of the Dutch West India Company in 1626.

MARK: When the British took over, New York became even more reliant on slave labor, so that by 1703, New York City had the second highest proportion of slaveholding families in the colonies, after Charleston, South Carolina.

MAX: After the American Revolution, New York State passed a series of gradual emancipation laws starting in 1799. And in 1838, a free Black man named James Weeks bought two plots of land in Brooklyn. He wasn’t the first, but he got his name on the place.

MARK: The men like James Weeks who came to Central Brooklyn and started buying land, subdividing it, and selling to other free Black men -- they hoped to create a social and economic refuge for Black people from an unfriendly white world.

ALPHONSE FABIEN: That's what the original land investors had in mind like some sort of free space a safe space for Black people in this country.

MARK: But it wasn’t an entirely separatist project; owning land in Brooklyn would also enable them to take part in politics. According to the 1821 state constitution, for free Black men to vote they had to own at least $250 worth of land.

ALPHONSE FABIEN: This is a very vibrant self-sufficient community in the 1860s and 1870s.

MARK: As a self-sufficient community, they established a number of institutions.

ALPHONSE FABIEN: Churches. An orphanage. A home for the elderly. Cemetery. Insurance companies. Their own newspaper. Later on their own baseball teams.

MARK: There was the headquarters of the African Civilization Society, a “Back-to-Africa” movement 70 years before Marcus Garvey came along.

MAX: And a few doors down from that, there was a school.

MARK WINSTON GRIFFITH: So we're looking at a concrete wall that says no dumping do not trespass do not litter do not graffiti. It's got barbed wire on the top. And I believe it's a New York City Department of Transportation uh depot of some kind. It takes up damn near an entire city block and it looks pretty impenetrable. I'm sort of taking in the I don't know what you want to call irony or whatever of this site.

MAX: This is the site where Colored School #2 - the second school for Black children in Brooklyn -- was located as of 1847.

MARK: We do know that language has changed around this, but we’re going to roll with what they used back then.

MAX: The earliest free Black schools in New York City were in Manhattan, and they were developed by I guess what we might call “benevolent whites.” But Brooklyn was different.

MARK: We don't know exactly who started Colored School #2, but we do know that they were connected to a network of Black leaders who were actively cultivating these schools as an expression of community uplift.

JULIA KEISER: I actually have some pictures. But I know this is audio so.

MAX: Julia Keiser is the collections manager at the Weeksville Heritage Center.

JULIA KEISER: It was a small school and it was mixed ages. Like when you see those pictures of like the country schoolhouse. That's kind of what it was like.

MARK: When we think of all-Black schools now, we immediately associate them with overcrowding and bad quality -- less than the white schools. But by all accounts, the colored schools in Brooklyn served their students well.

MAX: The principal of Colored School #2 for many years was Junius C. Morel.

JULIA KEISER: He had been enslaved and he went to Philadelphia. He was very active in Philadelphia. He was active in the colored conventions movement. He was a writer.

MAX: From Philadelphia he went to teach in Albany. But then Albany public schools were integrated.

JULIA KEISER: In the process of integrating their public schools all of the teachers that were in that Black school lost their jobs.

MARK: At Colored School #2 they were having debates and discussions that would sound familiar to us today.

ALPHONSE FABIEN: They were asking themselves should they integrate into public schools and while others say no we need to keep our colored schools. We just want the same resources as the other schools have.

JULIA KEISER: Why are you laughing.

MARK WINSTON GRIFFITH: I'm just laughing because the debate you hear the same debate one hundred and fifty years later.

JULIA KEISER: And the language is the same too.

ALPHONSE FABIEN: And the language the same. Should we keep our kids in colored schools. Should the colored schools even have the name colored schools.

MAX: In 1869, Principal Junius C. Morel hired a white woman, Emma Prime, to be the assistant principal -- which set off a huge debate within the community. These quotes come from letters to a local newspaper at the time:

REVEREND BUNDICK: There were educated Black ladies compelled to accept menial positions at six or eight dollars a month, while here was a position one of them ought to have, held by a white woman. The taxpayers of Weeksville -- the colored folks -- supported this school and they ought to have Black teachers.

MR. CRUMP: The Board in its wisdom having selected a white teacher they were well satisfied with her, and to discharge her on account of her color simply, would place the colored folks in a strange position. She was laboring with success to instruct their children.

JULIA KEISER: And this is kind of in the context it's also funny because the colored schools actually had white students in them.

MAX: And they had for years. Julia read to us from a report from 1853:

JULIA KEISER: You'll have to excuse the language because it's old. “As has been before hinted some pale faced children attend this school. The committee observed four boys and one girl who were unquestionably of the pure Caucasian race besides several others of doubtful origin.” So at a certain point there was a debate about whether they should throw the white kids out of the school because it was like. Like if it's gonna be a colored school then maybe we need to actually move all the white students out.

ALPHONSE FABIEN: There was always a white population here in Weeksville. By like 1870 the white population and Black population they're nearly neck in neck with each other. And then later on the white population definitely surpassed it.

MAX: There was a huge wave of immigration from Europe, and more and more of these immigrants came to Brooklyn after the Brooklyn Bridge was built.

MARK: Meanwhile, Colored School #2 changed its name to P.S. 68, but it was still mostly Black, and still operated out of a kind of one-room country schoolhouse. So Brooklyn -- still at this time its own city, independent of New York -- was going to build them a new home.

MAX: But the nearby public schools were severely over-capacity, and local white families petitioned that they should get the new building. (They also argued, of course, that increasing the size of the colored school would decrease their property values.)

MARK: Under pressure from these parents, the Brooklyn Board of Ed gave the new building away to the white school, P.S. 83. Initially the building was quote-unquote integrated, in the sense that you had the colored school on the first floor, and the white school on the second floor. But inevitably, the colored school wasn’t getting the same resources as the white school, so families at the colored school came up with a plan to essentially integrate the schools by force. They decided to register, en masse, for the white school, not the colored school.

JULIA KEISER: But what that would have meant would have been the end also of Colored School Number Two.

MARK: And people had mixed feelings about that.

JULIA KEISER: There were concerns about the Black teachers concerns about the control over education and what it would mean to just be in a general school and not necessarily have that leadership.

ALPHONSE FABIEN: You know you probably going to think to yourself. Are there teachers that look like my son or my daughter. Um. Will they learn to take pride in who they are. But at the same time. Are these teachers competent. Will they learn skills. It's it's very very similar to what's going on today.

MAX: So the school was integrated! With an integrated teaching staff and integrated students and a Black woman as the assistant principal.

MARK: But the neighborhood kept changing. We went for a walk with Alphonse, through the neighborhood once known as Weeksville.

ALPHONSE FABIEN: This is like the hub of Weeksville. Like so this there's the corner of Troy and Dean Street. This right here behind you guys. As you see it says Public School 83. Yeah. Yeah right there.

MARK: It’s an imposing building with carved stone around the windows and doorways.

ALPHONSE FABIEN: It's abandoned now. Broken windows. Public School 83.

MAX: It’s about to be turned into apartments.

MARK: In the 1800s, Black families in Weeksville had owned homes and land, which they used for farming and raising animals. But with the turn of the century, as the city became more and more urbanized, and more and more European immigrants moved in, Weeksville lost its independence. Homeownership and job opportunities declined. Most of the Black institutions of Weeksville closed or moved away, and Weeksville itself was mostly forgotten.

MAX: So even though Weeksville is now basically considered a part of Bed-Stuy, or at least Bed-Stuy adjacent, Bed-Stuy has its own history. After the break.

MIDROLL BREAK

ANTHONINE PIERRE: Hi. This is Anthonine Pierre and I’m the deputy director of the Brooklyn Movement Center, which Mark told you about a little bit earlier. BMC does a ton of community organizing work in Central Brooklyn on issues like police accountability, housing justice, food sovereignty, and environmental justice. School Colors is produced by BMC’s citizen journalism project, Brooklyn Deep. If you like what you’re hearing, and you want to support Black-led organizing in Brooklyn, including dope podcasts like this, head over to the School Colors website at schoolcolorspodcast.com and click Support.

BEDFORD-STUYVESANT

MARK: The neighborhoods just north of Weeksville started to become a magnet for Black migrants from the South just after World War I. At first, they were two distinct neighborhoods: Bedford and Stuyvesant Heights. As they got blacker, the neighborhood was increasingly referred to as one -- Bedford-Stuyvesant -- to geographically and linguistically contain the spread of Black people.

MAX: Migration to Bed-Stuy really picked up when the new A train along Fulton Street allowed Black refugees from an overcrowded Harlem to make their way to greener pastures here in Brooklyn.

MARK: That A train was so important to Black life in New York City, it got its own song.

ELLA FITZGERALD: You must take the A train / To go to Sugar Hill way up in Harlem. / If you miss the "A" train / You'll find you’ve missed the quickest way to Harlem.

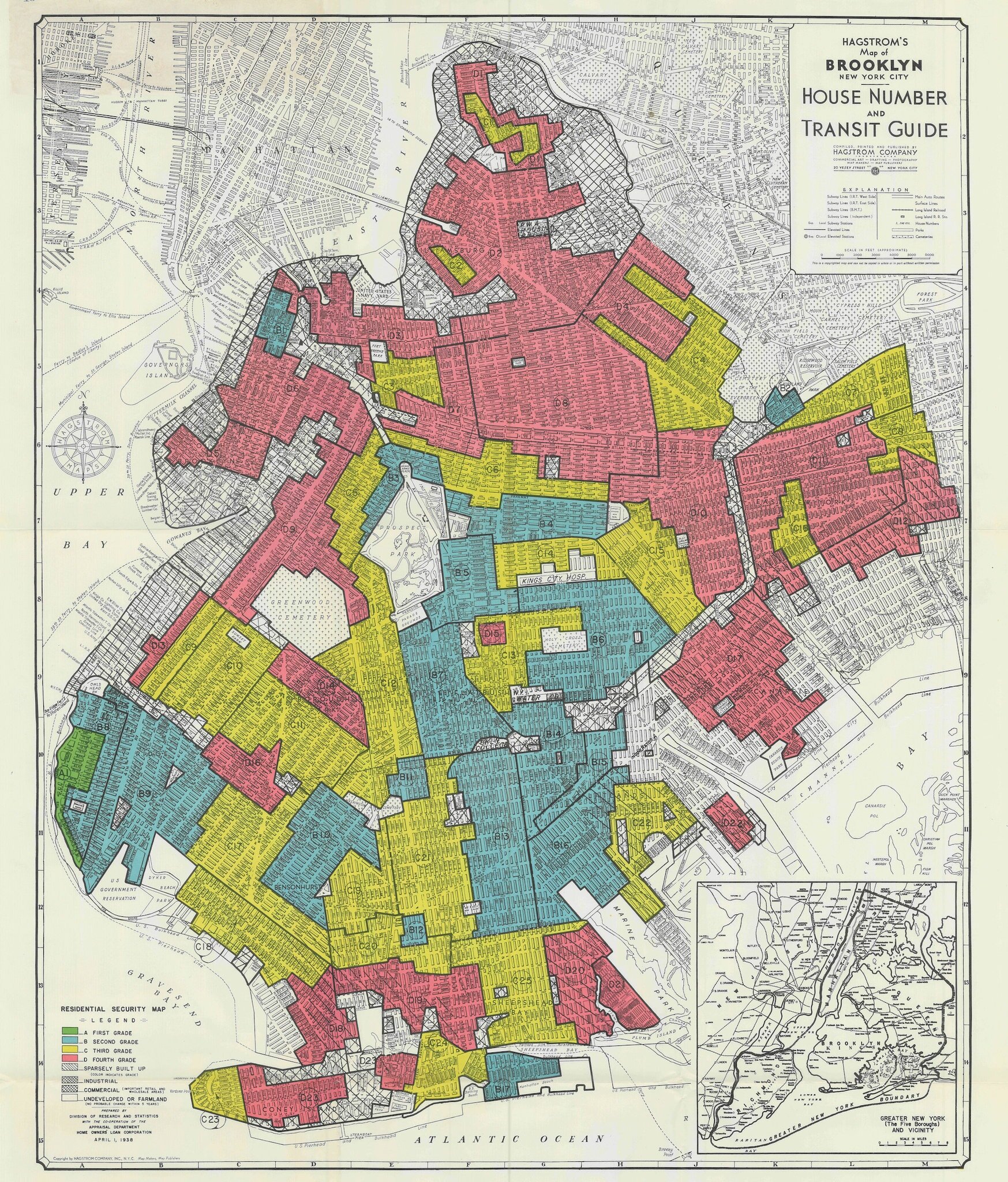

MARK: For a while, though, Bed-Stuy was racially integrated. What changed that, was redlining.

MAX: When I learned about white flight in school, I learned about it as a process that only started after World War II. And as the term “white flight” implies, all the responsibility was laid at the feet of individual white families who fled the cities to the suburbs. The real story actually starts about a decade earlier, and - surprise surprise - centers on some shady backdoor deals.

MARK: To try to get us out of the Great Depression, the federal government agreed to insure mortgages, to get banks to start lending money again and get the economy going. But the feds wouldn’t put their money behind just any old loans. So in hundreds of American cities, local real estate and financial interests got together to draw up maps that would show where it was safe and unsafe to lend.

MAX: Each neighborhood was given a letter grade; each letter grade was indicated by a color on the map. A was green, B was blue, C was yellow, and D was red. (That’s where the term “redlining” comes from.)

MARK: In all of Brooklyn, there was only one green neighborhood - and it was where nobody was living and nothing had been built yet - so there was limitless potential to make money. The implication being: the presence of any people at all would bring value down, and some people more than others.

MAX: Along with the map came a description of why each area received its grade - frequently citing racial and ethnic makeup. In D-rated neighborhoods, they’d say things like “Negro concentration” or “Influx of Jews and communists.” It wasn’t subtle.

As a result of this, the white people who could get out, got out. And the people of color who couldn’t, didn’t. And for those left behind, it became almost impossible to buy or maintain a home.

MARK: All this got much worse after World War 2. Hundreds of thousands of Black Americans came to New York from the South as part of the second Great Migration, fleeing racial terror and looking for factory jobs. When they arrived, the handful of neighborhoods where they clustered — like Harlem and the “Harlem of Brooklyn,” Bedford-Stuyvesant — were at the center of a perfect storm of disadvantages.

MAX: The manufacturing jobs Southern migrants had hoped for were disappearing into the globalized labor market. White people were leaving for the suburbs, with the help of the G.I. Bill and the federal highway program. And with the white people went essential city services. Quote-unquote slums were cleared to make way for modern public housing, but the modern public housing was built on the cheap and never properly maintained.

MARK: And thus… Bed-Stuy became known as a ghetto.

ADELAIDE SANFORD

MAX: Dr. Adelaide Sanford was born in Brooklyn in 1925. Before the war, before the depression, before redlining. She’s 93 years old.

ADELAIDE SANFORD: It's hard to know what's happening today if you don't understand what preceded it how we got to this point.

MAX: And that’s exactly why we wanted to talk to her.

MARK: You might call Dr. Sanford the Dean of Central Brooklyn education. People around here talk about her with reverence. She was a teacher and principal in this district from 1950 until the mid 80s, and after that served on the state Board of Regents until the mid 2000s. So she’s been here through everything.

In fact, she grew up just down the block from the Brooklyn Movement Center, right there on Decatur Street. She now lives in a condo building outside Philadelphia, which is where we went to meet her.

MAX: Her apartment is filled to bursting with art and artifacts of a long and well-traveled life. In one of the more recent photographs, there she is on the Edmund Pettus Bridge with President Obama for the 50th anniversary of the march on Selma, Alabama.

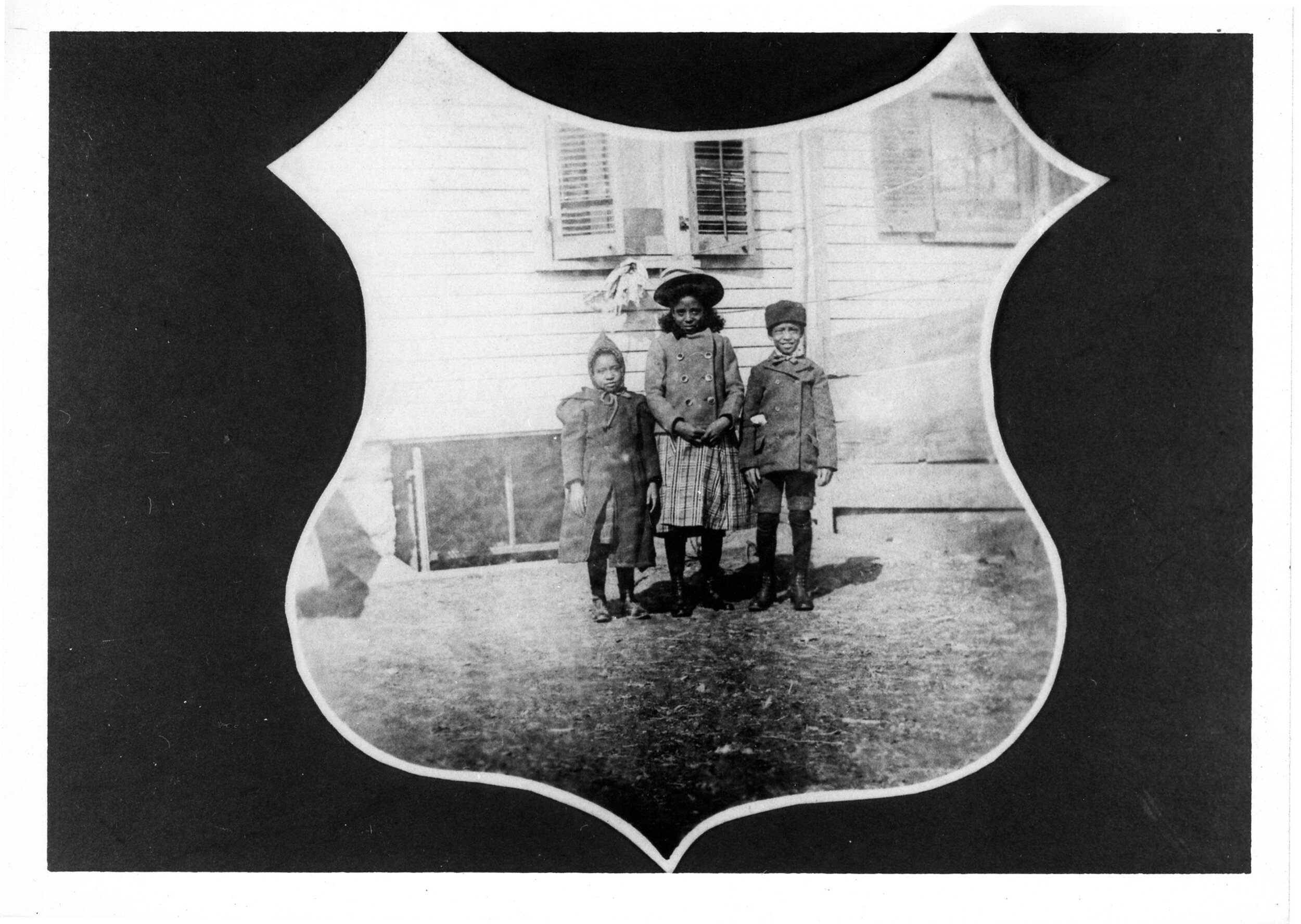

MARK: As she was leading us to the living room, I stopped at what must be one of the very oldest photographs in her collection.

MARK WINSTON GRIFFITH: Those your—

ADELAIDE SANFORD: Yeah my grandparents. My grandparents and my parents. I'm fortunate to have those pictures.

MARK WINSTON GRIFFITH: Wow.

MARK: Her grandparents were chattel slaves.

ADELAIDE SANFORD: I knew both of them in my lifetime. And I can never forget the impression that they had on me and the stories that my grandmother could tell me.

MAX: I don’t know about you, but it really puts things in perspective for me to spend time with someone who knew people who were enslaved. This past is not so far past as we like to think.

MARK: For real.

ADELAIDE SANFORD: I know District 16 because when I started teaching in 1950 I started in District 16 and I stayed there the whole time.

MAX: Her first teaching job, in 1950, was at P.S. 28. The first class she was given was called an “opportunity class.” It was made up of boys in grades four five and six who were considered uncooperative.

ADELAIDE SANFORD: The children in this particular opportunity class told me that I wasn't going to be able to stay because they had uh kicked the hell out of the other teachers that were there and it was sort of a sport to them. So they contrived various ways of getting me to give up you know.

MAX: She was warned by the principal to keep her head down and not expect too much progress. That wasn’t her job.

ADELAIDE SANFORD: He just wanted them kept quiet. And that was my first shock to understand that there were no expectations for these children.

ADELAIDE SANFORD: So that was the kind of climate that I went into which was very different from the educational experiences that my aunts had had who were teachers in Mississippi Vicksburg Mississippi when the expectation for children's progress was high. Every parent expected that his or her child would graduate from high school. Graduation from high school was like a celebration everybody went whether they had children or not.

MARK: Because her aunts had been teachers in the segregated schools in the South…

ADELAIDE SANFORD: I knew the power that a liberating education could provide for people who had been oppressed and depressed and and isolated. And so teaching to me was pivotal to getting children to understand who they were and why they were in the situation that they were in.

MARK: With this mindset, she eventually won over the kids in this opportunity class, who taught her as much as she taught them.

ADELAIDE SANFORD: It was the best educational lesson that I ever had. In spite of having degrees from Brooklyn College and Wellesley College. Those children taught me that we want to know about ourselves. We want to know that we're valued that our words mean something. And that's still true today.

MARK: From P.S. 28 Dr. Sanford went to P.S. 21: a new school built to serve the children of a new public housing complex, the Brevoort Houses.

But there were more children in those houses than the Board of Ed had planned for. So the school opened in 1956 on a half day schedule; they couldn’t fit all the kids in the building at the same time. Dr. Sanford tried to talk to the Board of Ed’s planners about this:

ADELAIDE SANFORD: And they said oh in 20 years the school will not be overcrowded. So we can't make a school bigger or take less children. We have to live for the 20 year time. And I said 20 years the life of children. What does that mean. But that was their decision. What kind of effect did this have on the children. What did it mean to their lives. Was not considered.

MARK: That’s horrifying to me.

MAX: Yeah. And when she petitioned the Board of Ed to at least have something on these children’s records to indicate that they had never had a full day of school, the Board of Ed said no. So they went into middle and high school at a deficit — through no fault of their own — with no explanation.

ADELAIDE SANFORD: And that again was a pivotal moment for me to understand that the system protected itself. At the mercy of the children. So that really became the basis of my efforts over all the years to see that there was some some change but that change was resisted with passion with tenacity with money.

MAX: Children in Bedford-Stuyvesant were not only suffering from overcrowding, but from poor instruction - poor instruction rooted in how the mostly white teachers saw their mostly Black students.

In the early 60s, Dr. Sanford was leading a professional development for other teachers in the neighborhood, when a white teacher stopped the lesson to challenge her. This woman said:

ADELAIDE SANFORD: That I was an apologist for the children that they were not deprived they were depraved. That's her quote. No one from her school raised an objection or said oh you know we don't all feel that way or that's just her opinion. It was nobody seemed to have been shocked.

MAX: But Dr. Sanford was not about to let that comment stand.

ADELAIDE SANFORD: I said well what exactly do you mean. And she began to describe her family and their experiences. That they had come to America. They worked hard they had sacrificed they did all the right things they didn't get into criminal behavior and they had done so well. And uh my people had not, And so I proceeded to point out the differences in our families. Said you came. You kept your language. You kept your religious traditions. We did not have that opportunity. She reported me as having insulted her. And I was asked to apologize by the principal of the school by the superintendent by the Union.

MAX: She refused to apologize.

ADELAIDE SANFORD: I was told if I kept my license I would never go beyond being a teacher.

MAX: Instead, she became the principal.

ADELAIDE SANFORD: After much racial opposition. From the Union and from the teachers that were there who felt that I was a revolutionary that I was a troublemaker.

MARK: There were very very few Black supervisors in New York City schools at the time, and none whatsoever in District 16. So once she was in leadership, she had some tough fights ahead of her.

At the time, the school was still celebrating Christopher Columbus and George Washington, which she could not abide.

ADELAIDE SANFORD: These were the pictures that were in the auditorium when I became Principal. I took all of them down.

MARK: And not without resistance from her own staff.

ADELAIDE SANFORD I was grieved. The union grieved me. The Italian teachers grieved me because I said that Columbus didn't discover America. So the effort to tell the truth was not central.

MARK: The teachers’ negative attitudes towards the students extended to their parents, too. And it came from the top. She remembers hearing a district supervisor telling teachers:

ADELAIDE SANFORD: Everything that these children know of value will come from you teachers. Because their families have nothing to offer them. So it was pervasive it was everywhere.

MARK: So as the principal of P.S. 21, she decided it was not only her job to be the instructional leader for the school, but to be an advocate for her parents -- nearly all of them Black, nearly all from the projects.

ADELAIDE SANFORD: They had nobody to go to about any of this. The teachers had unions. These parents had nothing. I mean who do you go to. The superintendent. The superintendent knew that these attitudes prevailed. When I had gone to the superintendent about uh the children not having books in the classroom it had been so what's new. There just were no expectations.

MARK: Like a true organizer, she first had to help the parents to be dissatisfied with their condition.

ADELAIDE SANFORD: To say this is not an acceptable situation you can not be satisfied with you child's three hours of instruction. People asked me why did I stay. I was there 20 years. It takes a while. You have to change a whole generation of thinking of people who have accepted their condition. I couldn't I couldn't live with that thought.

SCHOOL INTEGRATION MOVEMENT

MARK: To relieve the overcrowding at P.S. 21, Dr. Sanford and her parents successfully pressured the city to add a wing onto the building.

MAX: But public schools in Black and Puerto Rican neighborhoods all over the city were overcrowded and underfunded. Many people believed the solution to these problems was school integration.

MARK: In September 1959, the Board of Ed bussed the very first group of 300 Black students to white schools: from Bedford-Stuyvesant in Brooklyn to Ridgewood-Glendale in Queens. And, of course, with the first group of Black kids to be bussed, came the first organized white opposition.

MAX: Parents and community leaders in Ridgewood-Glendale organized a boycott of five elementary schools at which these Black elementary school students were supposed to enroll. On the first day of school, almost half of the white kids stayed home. This was an omen of what was to come.

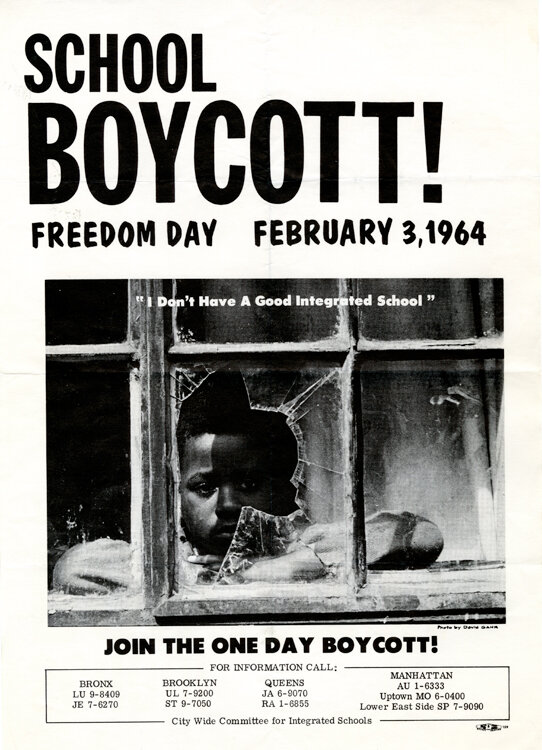

MARK: By 1964, New York City schools were more racially and economically segregated than they had been a decade earlier. So the integration movement decided to go big. On February 3, they staged the largest civil rights demonstration in American history up to that point.

STUDENTS: Jim Crow must go! Ole ole! Jim Crow must go! Ole ole!

MARK: Almost half a million students stayed home from school to demand a citywide plan from the Board of Education to integrate the schools. One of the organizers was Rev. Milton Galamison, a Black minister from Bed-Stuy.

REV. MILTON GALAMISON: Nobody can do these children more harm than these children are being done every day in this public school system. And in my opinion the refusal of the Board to already have taken immediate steps to correct these evils is a disgrace and a crime.

INTERVIEWER: And what are your hopes as far as the results of this boycott?

REV. MILTON GALAMISON: Our hope is that the board of education will decide to come up with a really comprehensive plan for citywide school desegregation and with a reasonable timetable.

INTERVIEWER: And perhaps if this fails, what next from here?

REV. MILTON GALAMISON: It will not fail.

INTERVIEWER: Thank you very much, Reverend.

MARK: But it did. The boycott failed. Despite mobilizing hundreds of thousands of people, the integration movement failed to get the Board of Ed to commit to a comprehensive citywide plan.

MAX: There was massive organized resistance from white parents -- most notably a new group called Parents and Taxpayers.

WHITE PARENT: Well we feel that we can prove as much as our oppenents who use the same tactics. We feel we have as much right as they. These are our civil rights and we’re taking advantage of them.

MARK: But resistance also came from within the central education bureaucracy. Galamison was pretty bitter about it.

REV. MILTON GALAMISON: Every time we brought in a teaspoonful of integration, the Board of Education threw it out by the shovelful.

MAX: To give just one example of this: I.S. 201 was supposed to be a new integrated school in East Harlem; when it opened in the fall of 1966, the district superintendent said, “Yes, it will be integrated - 50% Negro and 50% Puerto Rican.”

MONIFA’S STORY

MAX: Meanwhile, the city continued allowing Black students from overcrowded schools to elect to transfer to majority-white schools with available seats. One of these students was Monifa Edwards.

In the fall of 1966, Monifa was in the sixth grade, her name was still Cherylle, and she was bussed from Central Brooklyn to a predominantly white neighborhood way down in South Brooklyn called Gravesend.

MONIFA EDWARDS: Going out to Gravesend was deemed next best possible step in my education. Which. That’s what my parents lived for. Me getting the best education possible.

MAX: One afternoon in October, school let out for the day, and she and her fellow Black classmates piled back into their yellow school bus and waited to go home.

MONIFA EDWARDS: We were sitting, and we were sitting, and we were sitting. The matron’s not there, then we realized the bus driver’s not there.

It seems like from all directions, up the side streets, there are a crowd of people coming, so it was like a spontaneous protest on their part. And we’re talking about the mothers with the rollers, and. You know it was basically Italian and Jewish. And they were just. Coming toward the bus then they surrounded the bus and the bus was being shaken back and forth to the point that we truly felt the bus could be tipped over.

They were saying you know. “We don’t want those n***ers here, we don’t want them with our children.” You know.

So it was like a tsunami had come at the bus, and the bus was being tossed to and fro and then it just eased down and they parted.

So that’s how my nightmares were. Just seeing the faces. Especially one woman with her curlers on, oh my gosh. I could see her tonsils. She was screaming so loudly and broadly.

MAX: At first, she didn’t really know how to understand what had happened to her that day on the bus.

MONIFA EDWARDS: I relayed the story to someone and said well why did those people do that? And I was told oh, because they’re the devils. And I was like “Yes, you got that right. Now I understand.” It clicked. Because who else but a devil could shake a school bus full of children?

MAX: After this, Monifa took the train to school for the rest of the year.

MONIFA EDWARDS: At the end of the school year, I declared I was no longer going to that school, I had dutifully done my job, I completed the year, and I told them they could kill me whatever. But I was not going.

MARK: Like a lot of Black kids and families at the time, Monifa felt like she had to choose between going to a school where she might not learn anything and a school where she would be hated. But after what had happened on the bus, it was an easy choice.

As the sixties wore on and the energy was shifting nationally from Civil Rights to Black Power, a lot of people were convinced by experiences like Monifa’s that integration was not the path to Black liberation.

As for Monifa herself, she went to Junior High School 271: right on the border of two Central Brooklyn neighborhoods: Ocean Hill and Brownsville.

MONIFA EDWARDS: I was going to the neighborhood school and that was my neighborhood school. And I didn’t care as long as it was not in Gravesend.

MAX: Little did she know that Junior High School 271 was about to be at the center of a storm that would engulf New York City. Ocean Hill-Brownsville was the site of a bold experiment in community control of public schools. But that experiment triggered the longest teachers’ strike in American history.

MARK: What happened in Ocean Hill-Brownsville, and because of Ocean Hill-Brownsville, would fundamentally transform New York City schools, and the city itself.

MAX: And Monifa Edwards was there.

MARK: Next time, on School Colors:

LESLIE CAMPBELL: There was no teaching going on. The teaching had just stopped.

RHODY MCCOY: They never intended for this pilot program, to have any meaning.

FRED NAUMAN: Somebody has to say something to the children that we are not the enemy.

AL SHANKER: And that's precisely why I'm going to stand up here.

WILLIAM BOOTH: Have we come to that point of a race war.

IRVING LEVINE: Is it true that the school decentralization fight in New York City is really a fight between Black power and Jewish power.

SUFIA DE SILVA: It wasn’t about learning to hate another culture or race. It was about learning to love your own.

VERONICA GEE: We’re children. Why do you have to have guns. Why do we need dogs. This is America!

MAX: School Colors is produced and written by Mark Winston Griffith and Max Freedman. Editing and sound design by Elyse Blennerhassett. Production associate Jaya Sundaresh. Original music by Avery R. Young and de Deacon Board. Additional music in this episode from Chris Zabriskie and Blue Dot Sessions. Recorded at Brooklyn Podcasting Studio.

MARK: School Colors is made possible by support from the NYU Metropolitan Center for Research on Equity and the Transformation of Schools and the Carnegie Corporation of New York.

MAX: Letters by residents of Weeksville come from Judith Wellman’s book, “Brooklyn’s Promised Land.” The letters were read for us by Liz Morgan and Omari McCleary. Learn more about the Weeksville Heritage Center at www dot Weeksville Society dot org.

MARK: Special thanks to Matt Delmont, Charlie Isaacs, Ilana Levinson, Katy Rubin, and Dr. Renee Young.

MAX: School Colors is a production of Brooklyn Deep. Follow us on Twitter and Instagram @BklynDeep. You can find more information about this episode, including a transcript, at our website, schoolcolorspodcast.com.

MARK: Brooklyn Deep is part of the Brooklyn Movement Center, a member-led organizing group in Central Brooklyn. Visit brooklynmovementcenter.org to join or donate.

MAX: You can also support School Colors by leaving us a review on Apple Podcasts, or telling a friend. Till next time -

MARK: Peace.